by Rachel Choo

The ancient Silk Road – actually a network of established roads, unkempt pathways and evanescent desert trails – conducted goods, ideas, adventurers, spies, diplomats and armies from China, across the Eurasian continent to India, the Mideast and Europe, and back. The road has become a fabled metaphor for cosmopolitan wayfaring and exchange, despite the fact that it was also a highway for brigands, barbarism, pillage, warfare, and conquest – no doubt elements which enliven the multifaceted history of the region through which it ran. Today particularly in relation to the rise of China there is talk of new Silk Roads, and an accompanying anticipation of the economic, cultural and geopolitical possibilities which they could bring, including those involving the Central Asian states lying at the nexus of these new roads – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

In this context one may speak of New Silk Roads: Painting Beyond Borders. In keeping with the idea of the roads as conduits of sophisticated exchange, one can begin to look to the Central Asia of today as providing a basis for such an exchange in the twenty-first century. Owing to its millennia of rich history and culture, its artists are able to use motifs from the region’s past and present to discuss their actual and projected journeys – physical, psychological, spiritual and metaphysical – to be taken within and beyond its borders. While the Central Asian artists featured in the exhibition New Silk Roads: Painting Beyond Borders mostly work in the conventional media of oil or acrylic on canvas as well as sometimes in combination with other media, the images they create are about going beyond – crossing borders – in various ways. They may go beyond the mundane, beyond type, beyond realism, form and recognition, beyond the literal, beyond the temporal, beyond the Self and life itself, and beyond expectation.

This essay deals primarily with the modern and contemporary art to emerge from Central Asia, with a focus on painting by Fayzulla Akhmadaliev (b. 1950) and Kadirov Gafur Kolbovich (b. 1958), both from Uzbekistan, Murat Hojakuliyev (b. 1969), from Turkmenistan, and Leyla Mahat (b. 1970), from Kazakhstan. It draws inferences about painting and the art in the region, as viewed through the lens of these practitioners. At the same time it attempts to ground an understanding of these artists, their work and the wider art practice in what are the realities of the region: its history, culture, religion, economy, demographics and geopolitics. It also explains what is fresh and exciting about this relatively unexplored field, and how it contributes to the international art scene. The artists are introduced, and themes and formal qualities in their work identified, as are continuities and innovations, and external and native influences.

Like a voyager on the ancient maritime Silk Road which ran parallel to the Central Asian one, Serbian-born Singapore resident Filip Gudovic (b. 1992), who has sojourned in Southeast Asia for over twelve years, adds another dimension to the idea of painting beyond borders. His work is viewed in the light of this sojourn and his own other psychological, spiritual and metaphysical journeys, and also in relation to the journeys of the Central Asian artists.

Modern & Contemporary Central Asian Art

Modern and contemporary Central Asian art is not confined to one dominant style, but instead draws upon a whole range of styles which have been considered modern by Western art historical discourse, from around the mid-nineteenth century till the present. It can also include references to styles or genres predating the turn of the modern in art, such as neo-classicism or history painting, and is additionally influenced by media such as commercial advertising and fashion photography, popular crafts such as decoupage, traditional Central Asian folk or applied art, or the decorative art of the Muslim world of which the region is part. Nor is modern and contemporary Central Asian art limited to the conventional major media of oil painting. Alternative media, including watercolour, silkscreen, embroidery and textiles, photography, video, light boxes, installation and cardboard, are frequently used.

Painting Beyond Borders

The focus of the New Silk Roads artists appears to be the annunciation of rebirth in various forms – that of the human soul and spirit after decades of atheistic communism, of the belief in the sublime, divine and immortal, of the Self and its moral and psychological sense, of the sense of tradition and nation, of magic, fantasy and yet thoughtfulness, and ultimately, that of life itself and the celebration of a rich and unique cultural heritage. Since the Bronze to the early Iron Age, Central Asia had rivaled the classical East (ranging from Mesopotamia to India) in the artistic and technical skills of its peoples. Today, artists working in the spirit of their ancestors and according to their particular aesthetic sense and outlook have given birth to new and unique interpretations.

Amongst the practitioners of this tradition is Akhmadaliev, who frequently produces works in which life appears to burst forth anew, through his various images and metaphors of the garden. His Girls in a Garden (2009) is a lush evocation of an abundant garden whose crowning beauties are its four reposing girls. The way the artist recounts the making of this work is almost reminiscent of the Biblical story of the Creation, where God forms Adam and Eve apparently as the summit of his labours – “the process of creating this painting was rather complicated and long; it seemed to be lacking something despite numerous amendments. Then [I] made up [my] mind to depict a mysterious world of girls in a garden. Thus was a deficiency corrected… only then did the painting acquire its real value”. The girls’ images, described as flickering, rather like figures in a darkened room illuminated by candle, seem to emerge from the dense, stylised but not stilted vegetation as the eye picks them out gradually but surely.

Hojakuliyev’s own Garden of Eden (2015) is a riotously colourful announcement of again, a new dawn. It simultaneously suggests the flurry of excitement accompanying a new beginning of creation, and yet also the pristine quality of this new garden, as symbolised by fresh colours and the flute – that most mellifluous but emotive of instruments played by Central Asian sheep and horse herders just as the Greek nature god Pan would play his flute. The momentum associated with rebirth spills over into the artist’s Moonlit Night (2015), which, rather than what one might expect of a work thus titled, is actually an almost diabolically energetic colourful salsa of a night.

In contrast Kolbovich’s Sunset (2014) is a much stiller image but is no less about life, with the sun on the landscape being for the artist both its symbol and his inspiration, and for us a reminder of the shamanistic tradition of Central Asia. The photorealistic style focuses the viewer on the scene rather than distracting him with technique. The idea of the land and nature as being life-giving and part of a local spirituality is embodied too in the waters of his placid Lake of Oblations (2003).

Native to this land is the ubiquitous horse, which in Central Asia for millennia has been vehicle, companion, lifestyle, livelihood and metaphor for many things, including Central Asianness itself. In Akhmadaliev’s Hunter from Issyk Kul (2010) a skilled cavalier perches hands-free on his mount, one hand holding his hunting bird and the other his dutar for entertainment away from home. The rider’s love of his horse is evinced in the artist’s careful ornamentation of the animal. In Memories of a White Horse (1992), the black and white horses stand respectively for the recollections of the personal experiences of evil and good, and naturally the desirability of the latter over the former. The horses here are symbolic figures in an adult’s dreamscape, whereas the hunter’s horse is much more of a historical entity playfully interpreted as for a child’s book.

Other mythic beasts inhabit this Central Asian artistic landscape. Akhmadaliev’s winged lion in The Unknown Artists of Bukhara (Sphinx) (2014) signifies the undying work of the artists whose legacy lives on in the beauty of every stone and mosaic of the built environment of one of the world’s most wondrous ancient urban centres. His human-faced Lion (1997), perhaps a kind of sphinx, implies strength and the fight for truth, but also a humanity descendent from the lineage of other great leonine figures of the East such as the Lion of Judah (Christ) and the Lion of the tribe of Shakya (Buddha).

Elsewhere in the exhibition, Gudovic’s insect-like objects in Meditating on K’s Tragedy (2014) lend a sinister overtone to what one suspects is an allusion to an anonymous rotting corpse – Salvador Dali meets shades of the American forensic crime-fighter serial. The Serbian’s semi-abstract but instantly recognisable orange cat in The Science of Cat and Mouse (2014 – 2015) may be depicted as perched and resting on a ledge, but its colour suggests the incredible automatic and machine-like energy evinced when the animal sees and pounces on a furtive mouse, here signified by the cryptic object-letter M. This is not so much an image of a particular cat and mouse, but perhaps rather a Platonic imagining of how the archetypal form of the cat would exist and behave in relation to the archetypal mouse.

The individuals who populate the imaginative landscapes of the artists are also types – sometimes mythic, at others more ordinary, but nonetheless all inscrutable to some extent. Kolbovich’s Custodian (2008) is a partly-shrouded Central Asian earth mother-like figure whose antiquity is as great as that of the land she guards. His human-angels in the surrealistic Dream. Innocence (2008) partake of a ritual of forgiveness, the cause for which is even less clearly defined than the bodies of the participants. His cubist Face (Self Portrait) (2008) is not a whole person but representative of one and its struggles to find a new sense of Self – perhaps one which is more organic to the land which gives it birth. This image dates from the same period as Loneliness (2008), another portrait of what is essentially the artist in a period of depression and unexplained but clearly visible mental disquiet, as denoted by the intense colouring and diagonal fracturing of the visual plane. In comparison the flurry of half-dry brushstrokes to suggest speed, impermanence and simply no time for what looks like an uneaten sandwich and covered Styrofoam cup on a desktop, in Gudovic’s Juggling Life of a Front Desk Clerk (2014), seems to portray the banal but nonetheless stressful lot of a junior bureaucrat. Ultimately the abstractness of the painting asks that the viewer pause for a more leisured contemplation and personal experience of what may be depicted and intended.

The presence of individuals is referred to even more obliquely, if shrewdly, in Mahat’s amulet paintings, which recreate ancient jewellery uncovered in archaeological digs and reconstructed by Kazakh scientists. Her images re-live the work of the archaeologists, who, as modern-day seekers of the nation’s past, have in their turn reprised the craftsmanship of the ancient peoples who populated the territory of present-day Kazakhstan. Artist, archaeologist and artisan are all connected through the materiality of the gold ornaments and their contemporary artistic representations, as well as by the land once inhabited by the ancient peoples which now forms their burial place and the physical basis of the modern state. The choice of depicting jewellery, the wearing of which was an aristocratic prerogative, is also suggestive of the lineage which the artist claims as validation for the modern state. The appeals to the forces of history and heredity are perhaps nowhere better illustrated than in Amulet and Colour (2014), where their potency seems to glow red-hot, their vividness embodying itself in the profuse viscosity of paint, tactile and Medusa-like in its writhing.

Hence the modern Central Asian nation-state can be considered as much of an imagined and spiritual space as a physical one. My Home (2015) – Hojakuliyev’s home and perhaps his country, is a beloved dwelling whose identity is simply hinted at by an arched window frame on the central object in his abstract composition. Yet at the same time this composition is reminiscent of a bird’s eye view of the cuboid Ka’aba, the House of God in the compound of the Al-Masjid al-Haram in Mecca, suggesting a spiritual or even religious element to this dwelling. The link between home and nation shows itself too in the way Akhmadaliev depicts his Central Asian subjects as if framed within the borders of antique house rugs in The Unknown Artists of Bukhara, Lion and Hunter from Issyk Kul.

Kolbovich’s Bukhara Triptych: Gate, Minaret Kalyan and Bukhara Lane (Dead End) (2001) is not a mere photorealistic depiction of familiar or exotic sights in Uzbekistan, but rather a series of tropes for the asking of questions such as where are we going? (the gate), what do we believe in? (the minaret) and are we proceeding the right way? (the overturned vase). The calmer, more pleasing palette and use of light in these pictures, as compared with the aforementioned works from the artist’s period of depression, signal the more restful frame of mind with which those metaphysical questions were conceived. His own sense of measured philosophical perspective is further conveyed through the portrayal of three vistas – the first on the unknown, the second on the infinite and the third on a dead end of a street.

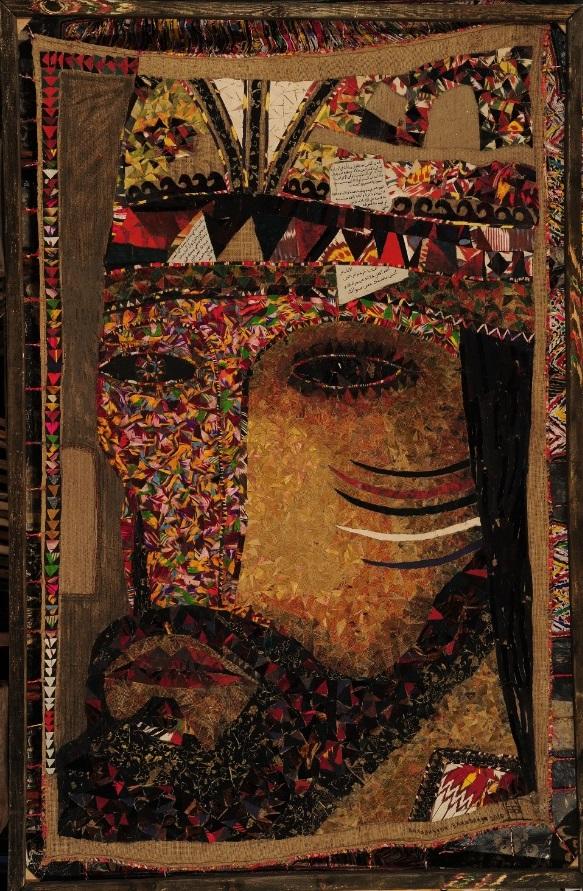

These themes are replayed in Akhmadaliev’s Baha-ud-Din Naqshband (2010), a portrait of a poor and lowly man who became one of the greatest of Sufi mystics. Its media is oil on hemp, the rough stuff of Sufi clothing, rather than canvas. The complex patterns on the face represent the spiritual richness of Baha-ud-Din’s interior world. His eyes twinkle in contemplation of our world, and the viewer of the painting is himself made to ask, over and above the superficial, where do I stand, on the way to perfection?

Fayzulla Akhmadaliev, Baha-ud-Din Naqshband, 2010, Oil, hand-woven cotton, hemp and additional media

The turn away from atheistic communism in Central Asia and Europe has also freed people to explore spirituality in less obvious forms, as with Gudovic’s series about machines and the taking of their essences as tools for “organising materials and flows”. The semi-abstract quality of his work, rather than limiting interpretation, actually widens the viewer’s scope for understanding what actually happens when for example, one dreams (Dream Machine, 2014 – 2015), or it rains (Raining Machine, 2014), or a desk clerk works (Juggling Life of a Front Desk Clerk). Such phenomena are to be understood as working or perhaps unsuccessful processes with many complex components, as denoted by various colourful and sometimes distinguishable machine-esque parts.

New Silk Roads

In conclusion, the artists of New Silk Roads: Painting Beyond Borders are using, adapting, re-exploring and drawing parallels with various themes, styles, genres, aesthetics and approaches. Their subject matter echoes sources as diverse as Islamic, Judeo-Christian and Buddhist religion, as well as historical, cultural, scientific and personal experience, myth and tradition, Greek philosophy and primetime television, dreams, nightmares and office work. Their ideas are executed in modes showing influences from the abstract to the naïve to the photorealistic to the symbolist and surrealistic, to Central Asian carpet-making and the architectural.

Nevertheless in a sense, none of these artists is overly concerned with “catching up” with the world, in the manner of say, contemporary Chinese artists, who by their very commercial and/or critical success have become a kind of touchstone for what the artist should be, that is, overtly (if not admittedly) politicised and often esoterically intellectual. In the case of the Central Asians there is still a preference for using indigenous motifs: the “curtain” of suzani cloth with its traditional Uzbek patterns in Girls in a Garden, local animals, objects, symbols, landscapes and personalities which are not part of a globally recognised regional artistic tradition – as yet. Nor are they fearful of using conventional and even whimsical concepts of beauty, or notions of tradition and spirituality in their art, which are often avoided in the most cutting-edge of Western or Chinese contemporary art. The work of these artists therefore has strong visual appeal in addition to those of the intellectual and spiritual. With Gudovic, the sense of the dispassionate artist-observer comes through in his choice of the aesthetically philosophical subject-matter of the nature of the machine, rather than in the promulgation of a political cause. If at all any of the Silk Roads artists are politicised, it is in the most discrete and genteel rather than radical of ways. Instead of the blatant pinpointing of any dysfunctions or deficiencies, these artists speak instead of ideals – in aesthetics, in the form of new beginnings, in personal quests for spiritual and metaphysical betterment, in role models and special geographical places, things or concepts, the latter for example being demonstrated by Hojakuliyev’s portrayal of Motherhood (2015) as a variously joyous, energetic, complicated and perhaps chaotic state.

The fresh yet universal qualities of the art of New Silk Roads ask that the viewer expand and intensify his ways of seeing. This is work requiring patient contemplation, which should itself engender further curiosity, questioning and exploration of new artistic and other terrains, rather than presenting pat and ready answers. In the case of the Central Asians the revival of aspects of their traditional cultures fuses in complex ways with a myriad of contemporary themes, which given their several thousand year-old heritage is unsurprising. With the maritime Silk Road sojourner Gudovic the attitude of an accustomed traveller correlates with an artistic emphasis on seeking new horizons in the ordinary and everyday.

All the artists continue to capitalise on the new advantages and challenges of living in complex, contemporary globally-influenced but tradition-rich societies, and their works hold the promise of future experiments in form, theme and approach which will likely lead to new directions and frontiers in the global contemporary art scene. In the way that Samarkand and Bukhara in Uzbekistan have survived two-and-a-half millennia of existence, through invasion by ancient and modern forces such as those of Alexander the Great, the Umayyad Caliphate, Genghis Khan and the Red Army, to emerge respectively as among the world’s most historically rich and architecturally resplendent cities, the works of the artists presented in New Silk Roads: Painting Beyond Borders dip into historical, cultural, philosophical and spiritual wells to supply the viewer with refreshment aplenty for the exploration of the world around us from exciting new perspectives.

Rachel Choo graduated from the M.A. Asian Art Histories programme in 2014.

This essay was originally published in the exhibition catalogue of New Silk Roads: Painting Beyond Borders, an exhibition introducing modern and contemporary art from Central Asia curated by Sally J. Clarke, Co-Founder ENE Central Asian Art and held from 21 April to 27 2015 April at ION Art Gallery, Singapore.

All images courtesy of ENE Central Asian Art