With the reopening of borders after a long COVID-19 hiatus, the choices available to our cohort were significantly greater than those of the past two years. Ultimately, the decision was made to travel to Bangkok, Thailand, to coincide with the Bangkok Art Biennale (BAB). The theme for this edition of the BAB, Chaos:Calm, is a fitting response to the uncertainty we experienced in the last two years. Apart from COVID-19, we have witnessed an increase in extreme weather events worldwide, a surge in hate crimes, and growing political polarisation. Chaos reflects the worldwide state of affairs, but in spite of that, there is also a search for peace and tranquillity, a calm respite from the madness. Although these two concepts may appear to be in binary opposition, the artworks showcased in the BAB often explored the serenity that arises amidst chaos or seek calm and serenity within chaos.

Our first encounter with the BAB took place at the Bangkok Arts and Cultural Centre, a sprawling, multi-leveled art complex that spirals upwards many stories. Upon entering, we were greeted by Jan Kath’s (Germany) large-scale tapestries called Ice People, bearing imagery of war. From the narrow walkway, we looked up at guns, tanks, fighter jets, and bombs that were motifs in Kath’s artworks. However, rather than being an homage to war, Kath’s pieces take a personalised approach to war, specifically its effects on people. The combination of traditional patterns and colours in block shapes harkens back to traditional craft from Persia, which at its peak covered present-day Iran, Egypt, Turkey, and parts of Afghanistan, countries that are presently recognized as sites of war and violence.

Jan Kath, Ice People, 2022, textiles, Bangkok Arts and Cultural Centre. Image taken by Adeline Lim

We slowly made our way around the spiral, winding upwards from the 7th floor to the 9th floor. From a distance, we saw Vasan Sitthiket’s nang talerng puppets hanging on the walls. Titled Vladimir Putin, these puppets were massive effigies of recognizable, real-life political figures in various states of undress or tomfoolery. Intermingled with these figures were literal dickheads dressed in military gear, holding onto bags labelled with dollar signs or grabbing onto bombs and other weapons of mass destruction. Vasan Sitthiket’s critique is clear – these men are puppets of violence and their capitalist desires, at the expense of the rest of the world.

Off to the sides on the 7th to 9th floor were annexes that encircle the building. These spaces were pockets of peace and calm amidst the noise in the central atrium. Taking on a more contemplative and meditative approach, these works were often interactive pieces that encouraged visitors to the space to engage with the construction of meaning – taking time to touch, move, play with and just experience these works in very visceral ways.

On Day 2 of the Biennale, we headed to the Queen Sirikit National Convention Centre. The atmosphere was calm, and the halls seemed endless, with the gold finishing reflecting brightly in the morning light. This was in stark contrast to the chaotic hustle and bustle of APEC 2022 the previous month. As we entered the exhibition hall, we were greeted by Pinaree Sanpitak’s Temporary Insanity, a collection of stuffed fabric sculptures in warm, vivid hues of silk, commonly referred to as “breast stupas.” These dome-shaped forms came in various sizes and shapes, and as we approached them, we were encouraged to applaud. The more enthusiastic our applause, the more rapidly the sculptures vibrated. It was unclear if they were excited by our presence or stress-trembling in response. Nonetheless, these breast stupas swayed back and forth, performing vigorously as we clapped along. We became performers ourselves, reciprocating the dance that the sculptures were showing us.

Pinaree Sanpitak, Temporary Insanity, 2022, Textile and Electronic Parts, Installation, Queen Sirikit National Convention Centre. Image taken by Adeline Lim

Not all the works were loud and performative; some were quiet and contemplative, providing pockets of calm. For instance, Map of Memories by Qi Zhijie was a 7-panelled painting made with Chinese ink and pencil, resembling a map. This map attempted to document uncharted terrain – our memories. It identified the peaks of recollection and the valleys of amnesia and illness, giving tangible form to the landscape of our memory.

Even works that we expected to be chaotic, such as the minute dioramas by Jake and Dinos Chapman, were surprisingly calm as they were displayed in numerous smaller vitrines from various angles. Although the subject matter and violence in each work were chaotic, the bite-sized divisions somehow created a sense of tranquility in the room.

In the afternoon, we went to the Jim Thompson Arts Centre to see the Mit Jai Inn exhibition Dreamday, which was just a stone’s throw away from our hotel but still a considerable distance from our previous location. As is typical in Bangkok, we got caught in traffic and arrived embarrassingly late. Nonetheless, our curator-host Kittima was unfazed, accustomed to such delays. She took us through Dreamday and its two exhibition spaces. The first was a walk-through installation composed of long, painted strips of paper and canvas hung on walls or draped over a frame. We had encountered Mit Jai Inn’s work in Singapore during Singapore Art Week 2022, but with Kittima’s insight, we experienced his artwork in a completely different way. The second space displayed a series of painted rock-like forms and furniture scattered on a large table in the center of the room. These pieces could be taken home for continued display, creating an exhibition outside of the traditional gallery space. In homes, these works would take on new meanings and foster new conversations and unpredictable interactions with random visitors in a post-COVID world. We would have taken one ourselves, but the catch was that the artwork had to be displayed in a Bangkok-based home, and we weren’t sure if they would fit in our luggage.

Mit Jai Inn, Bangkok Apartments, 2022, papier-mâché stones, painted metal lamps, The Jim Thompson Arts Centre. Image taken by Adeline Lim

On our third day, we set off early to Ayutthaya Historical Park, a long ride. We made a detour to Bang Pa-In Palace first, however, where we were told that our dress code was inappropriate for the space, causing chaos. We were unsure of what exactly the issue was – was it our ankles, knees, or legs in general? It seemed like a very flexible definition, made more arbitrary because the only suggested solution was to visit the shops selling quick-fix garments that would allow us to enter the palace grounds. We declined and instead roamed around the grounds surrounding the palace, enjoying the riverside scenery and architecture of the houses facing us.

Ruins at the Ayutthaya Historical Park. Image taken by Adeline Lim

This turned out to be an excellent warm-up for the historic city of Ayutthaya. It was the second capital of the Siamese kingdom and was in its prime during the 14th to 18th century, at one point a cosmopolitan urban area and a center for diplomacy and commerce. However, by the end of 2022, the monumental architectural structures are now in ruin, having been beset by many wars and sieges. We arrived around 10 am and spent the better part of the morning wandering around the site. It was interesting to visualize what the place might have looked like in its heyday, though the reddish brick structures offered us no clues to their original surface finishing. As we wandered around the set paths, we were mindful not to trample on the conservation areas and tried to imagine ourselves walking the same paths as the Siamese people in the past.

We ended our day at the Museum of Contemporary Art, which was privately owned and featured the personal collection of eminent Thai businessman Boonchai Bencharongkul, showcasing his interests. Our visit coincided with a Banksy exhibition, though the wanton display of naked bodies on show stole the limelight for us. This divided our opinions – some of us were alienated by the lascivious nature of the works, while others found it a fascinating insight into the collector’s mind. Many works could be viewed through a sexual lens: lotus and bud-like forms were often viewed as breasts (perhaps encouraged by Pinaree’s work on day two). This permanent collection generated vigorous conversation regarding the nature of the works. One of the more interesting pieces was tucked away in one of the building annexes – a retelling of the Thai folk story Khun Chang Khun Phaen from two different artistic perspectives. A popular story, the character in the middle of the love triangle bears an uncanny likeness to Boonchai Bencharongkul’s sixth and most recent wife, actress Bongkoj Khongmalai, perhaps as a cautionary reminder of what happens to women who are undecided about where their true affections lie.

On day four, we had a more peaceful and intimate experience. We visited Pinaree Sanpitak at her charming home and studio space, where she was working on a forthcoming collaboration with Valentino that would be presented at The Warehouse Hotel in Singapore. We chatted about various topics, and it was fascinating to learn how her experience as a mother greatly influenced her artistic practice. Rather than being objectified or representative of gender, as we had discussed on day two, her breast stupas were more like life-giving forms that provided sustenance, nourishment, and care.

Pinaree Sanpitak in her studio. Image taken by Jeffrey Say

Later in the day, we had tea with Manit Sriwanichpoom, also known as the Pink Man, at his studio filled with walls painted vivid shades of pink, blue, and green. He spoke about art, politics, consumerism, and what it meant to be a contemporary Thai artist. What was intended to be a brief visit ended up lasting all afternoon, and we lost track of time as we enjoyed tea and biscuits on the top floor of his studio, only noticing the changing light as the day passed.

Manit Sriwanichpoom in his studio. Image taken by Adeline Lim

On our last day, we only had time for a quick morning visit to the JWD Art Space, where we saw a small exhibition. One of the works was by Jompet Kuswidananto, titled The Prelude. It was a chandelier that had been dramatically smashed on the ground, its pieces scattered around in disarray. The chandelier was balanced at an angle, as if it had been cut down and abandoned on the floor, a victim of rioting and looting. It was a relic of a history that suggested the impact of Euramerican traditions and influences.

Jompet Kuswidananto, Love Is A Many Splendored Thing #1, 2022, Installation with Found Objects such as Piano, Chandelier, Glass, JWD Art Space. Image taken by Adeline Lim

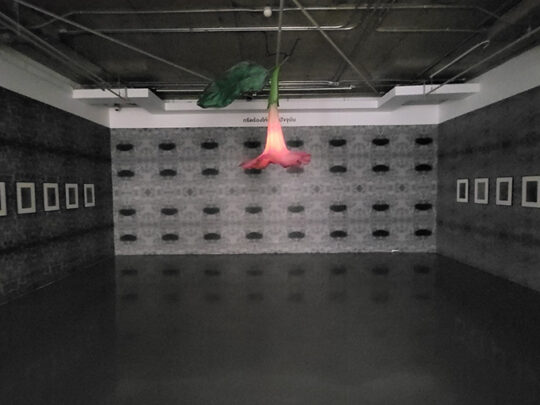

We were particularly drawn to an interactive work by Vadim Zakharov titled Scream… Scream.. Sing, which responded to the noise levels inside the gallery space. The louder the sound, the brighter the flower in the middle would glow, illuminating works on the walls. However, like the dog from Aesop’s fables, yelling at the flower and running to the walls proved to be fruitless as the light would fade before we arrived, and any glimpses of the works were lost to us. Only after some futile attempts, problem-solving and teamwork were we able to create enough illumination to view the images within the space, though we could not be both producing the sound and viewing the images. Our knowledge of the images – chimney chambers of the German concentration camp of Sachsenhausen – was only through second-hand knowledge, which functioned as a tidy allegory for the fractured nature of research, information, and history surrounding the war.

Vadim Zakharov, Scream… Scream… Sing, 2022, Mixed Media Installation, JWD Art Space. Image taken by Adeline Lim

In conclusion, our time at the Bangkok Art Biennale was a whirlwind of fascinating and diverse experiences. We had the chance to explore the works of both established and emerging artists, and gain a deeper understanding of the local art scene in Thailand. The visit to BAB was particularly unique as the artists were selected through open call application, which allowed for a wider range of styles, practices, and ideologies to be showcased. It was truly a refreshing change from the typical invite-only exhibitions that can often become exclusive clubs. As we boarded our plane, we were left with a sense of awe and inspiration (and unease, anticipating the expectations for our thesis) for this dynamic and ever-evolving art scene.