by Iola Lenzi

In his latest novel Map of the invisible World, Malaysian author Tash Aw discusses selective amnesia in the context of Indonesian history. One of his protagonists notes that Europeans remember bad things, while Asians forget them-as a way of erasing pain-, concluding that “…to be ignorant of one’s true history is to live in a void…where you do not really exist…”. Thai art historian and theorist Dr. Apinan Poshyananda has also described the phenomenon in Thailand where for reasons of political history, this self-and-collective delusion is perhaps more acutely experienced than anywhere else in Southeast Asia.

Siam’s status as the single Southeast Asian country deflecting colonial rule during Europe’s 19th century imperialist grab is understandably a rominent feature of all Thai histories. Yet beyond this achievement is the conflicted reality of the deft political maneuvering that prevented subjugation, as well as Siam’s own ambitions of regional tutelage and expansion. The Siamese leadership’s (Kings Mongkut (1851-1868) and Chulalongkorn (1868-1910)) mid and late 19th century Western-inspired structural and institutional reforms (progressive Asian models did not initially exist, Japan opening from the middle of the 19th century and only becoming an influence on Siam in the early 20th century), coupled with economic concessions to the foreigners, precluded outside domination while also affording the Siamese elite an early perspective of Thailand’s evolving national identity in a global framework. Thus, though modern political-Thailand was not born until 1932 when a constitutional monarchy replaced the absolutist, one can argue that from the point of view of the elites, consciousness of a Thai national identity has been a feature of Thai historical narrative for close to a century. Excepting the Philippines, this level of national awareness in the first decades of the 20th entury was unique in Southeast Asia. More uniquely still, the nature of this national identity, self-examining more than driven by anti-colonial sentiment, has evolved quite distinctly from versions prevalent elsewhere.

Yet early reforms in Bangkok, and a would-be regionally-precocious instauration of features of civil society such as human rights and democratic institutions, were conceived and implemented such that they did little to change the lives of Thailand’s illiterate rural poor, or indeed its small urban middle-class. Traditional structures continued to conflict with modern ideas, the country fractured for all its modern history by sharply opposing tendencies that still today are responsible for political instability. As a result, the country’s constitutional period, characterized until very recently by a succession of repressive military regimes (18 coups since 1932) punctuated by brief episodes of democracy, has profoundly coloured Thai cultural discourse of the past fifty years.

It is no surprise therefore that visual artists of the last two decades have often been keen to engage the public on subjects associated with Thai society and its institutions. Only a handful however – a small but articulate coterie of practitioners of the generation brought up in the ideologically polarized 1960’s and 1970’s-, have consistently presented the specific role of history and memory as a means of reflection on –and a way toward improving- the current lives of their co-citizens. These include, amongst others, Vasan Sitthiket, Manit Sriwanichpoom, Ing K. and Sutee Kunavichayanont.

As well as addressing national history and memory with solo shows, these polyvalent artists have sometimes banded together to work on these topics as a group. Using different formal and conceptual strategies, their initiatives have not only left their imprint on Thai arthistory, but on Thailand’s contemporary social history as well.

Vasan Sitthiket is amongst Thailand’s most internationally-recognized social activists. The multi-disciplinary Sitthiket, as founder of the Artists Party, is now also a national politician, his ongoing and vocal defense of the downtrodden making him a force for social change far beyond his status as a cultural icon. Fearless even before Thailand’s relative relaxation of censorship in the last decade, his practice trains a critical eye on all aspects of Thai society including its oldest, historically enshrined customs and revered institutions. Concern for truth, historical record and memory, the latters’ relationship with the present and ability to teach for the future, are recurring themes of Sitthiket’s most powerful pieces. Several bodies of work however distinguish themselves from the rest in their specific regard for key episodes or figures of Thai history.

Vasa n Sitthiket

Thailand is the land of the Thai, Flesh and Blood, 1996

Mixed media on canvas

150 x 150 cm

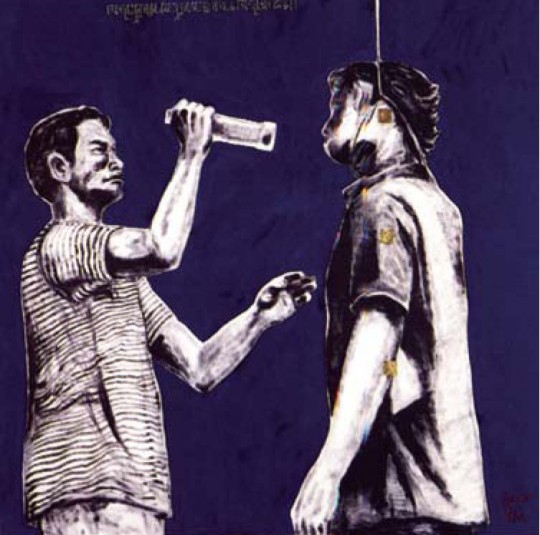

Barbarism and institutional moral corruption are conveyed with elegiac formal language in Sitthiket’s 1996 ‘Blue October’ series. Commemorating the rightist-instigated massacres of 1973 and particularly 1976, twenty years after the fact, Sitthiket consigns to large-format canvas scenes of police brutality and mob violence documented in the press of the day. Depicting torture and murder in a sober, monochromeblue narrative idiom, these paintings are all the more shocking for their stillness and stark figuration. Disturbing in their uncensored recollection of history, they are also intensely beautiful in their icy execution and pathos for the victims, immortalized for ever. His formal treatment blurring to a certain extent the distinction between thug and victim (the latter adorned with small patches of gold leaf, badges of merit-cummartyrdom), the artist eschews the polarization between good and evil habitually present in his work, so avoiding facilely righteous moral judgment. More importantly, by deliberately employing a reductive iconographic style that reveals neither detail of place nor time, the artist stresses the event’s meaning in the larger historical context, the series condemning all gratuitous violence everywhere. By producing ‘Blue October’ some twenty years after the fact, Sitthiket not only commemorates the event itself, but also underscores the importance of history and memory as tools for current enlightenment and progress. As much about empowerment and individual choice as morality, this series speaks of all our futures as well as of Thailand’s past.

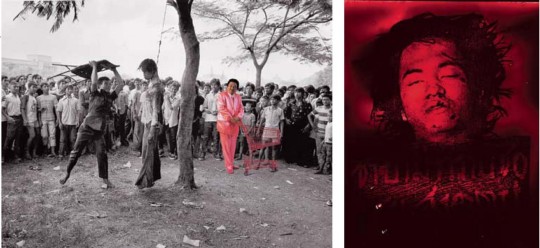

Some five years after Vasan Sitthiket’s ‘Blue October’, Manit Sriwanichpoom, Ing K., and Sutee Kunavichayanont conceived their seminal group manifestation “History & Memory”, put up at Chulalongkorn Universisty’s Art Center. Three bodies of work formed the show: Sriwanichpoom’s 2000 ‘Horror in Pink’, -referencing the same massacres, indeed the same series of period newspaper images employed by Sitthiket in ‘Blue October’-; Kunavichayanont’s ‘History Class (Thanon Ratchadamnoen)’ carved desk installation, and Ing K’s ‘Weeping Icon’ series of canvases. Launching such a thematically focused group show, the artists’ visual and conceptual strategies were geared to shaking public apathy and bringing history and memory back to the popular agenda. The three artists have mixed views regarding the success of the initiative in terms of public response. What is certain however is that ‘History & Memory’ was one of the more art-historically relevant exhibitions of the decade, establishing Thailand’s ability to produce contemporary art of visual strength, conceptual accomplishment and formal originality that articulating abstract ideas, could still speak directly to people beyond the confines of the elite art-gallery setting.

(Left) Manit Sri wanic hpoom

Horror in Pink # 1 (6 October 1976 Rightwing fanatics’ massacre of democracy protestors), 2001

C-print

120 x 165 cm

The incident photograph by Neal Ulevich – AP, Pink Man performance by Sompong Thawee

(Right) Manit Sri wanic hpoom

Died on 6 October 1976, 2008

Inkjet on paper

Sriwanichpoom’s ‘Horror in Pink’ was the most disturbing of the show’s three works. Appropriating the more than two decade-old black and white press clippings with their graphic display of violence and murder, Sriwanichpoom modified them with the insertion of his smug Pink Man-and-shopping-cart consumer icon, the altered images a macabre juxtaposition of the ironically allusive and the nauseatingly real. Contrasting the grisly reality of history and people who died fortheir ideals with today’s consumerism, the series offers a commentary on the vapidity and willfully delusional ignorance of contemporary Thai society. Thus, its manipulated newspaper photographs show that like Vasan Sitthiket, Manit Sriwanichpoom’s interest in these events has as much to do with countering the deliberate loss of historical memory pervasive in Thailand, as in recalling the event itself. These images also take aim at contemporary official histories that distort the meaning and circumstances of the 1970’s events. Addressing what Dr. Poshyananda has called Thailand’s ‘collective amnesia’, the series asks viewers to ponder the relevance of history in the crafting of contemporary Thailand.

The bulk of Sutee Kunavichayanont’s work, from his career beginnings in the early 1990’s to the present day, centers on the nation’s history, its ownership, and close relationship with national identity. History Class (Thanon Ratchadamnoen) of 2000 (and its subsequent variations), as it appeared in ‘History & Memory’, comprised 14 old wooden children’s school desks, each carved by the artist with a narrative scene from Thai history. Amongst the various episodes chosen by the artist, like Sitthiket and Sriwanichpoom, Kunavichayanont focused on the 1970’s massacres, reproducing in engraved form the notorious press photographs documenting the events. The artist however also cast his eye further back in time, illustrating key moments in 19th and early 20th century history (again quoting documentary prints and other period imagery) that viewed as a whole, succeed in shedding light on the nation in a fresh, non-partisan way. Further, not content to address educated gallery-goers with questions about the manipulation, distortion, rereading, and interpretation of history, the installation purposefully sought a wider public reaction, positioned as it was in the traffic-heavy open space opposite Bangkok’s Democracy Monument. Interactive, the work appealed to those who encountered it to take away a piece of history by encouraging all to make rubbings from the engraved desk-tops. Thus, viewers ‘returned to school’, making their rubbing to take home and prompted by the work to think not only about their own history in new ways, but their personal role in the building of the nation’s history. History Class, with its familiar form, public-space locus, and conceptual sophistication, despite its complex, multi-stranded reach, was able to provoke thought and response in a large and mixed audience.

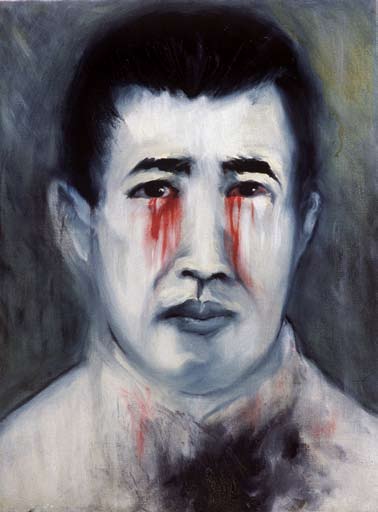

Ing K’s ‘Weeping Icon’ paintings used straight narrative to lyrically expose the evils of history. Her icons from the past –Kings Mongkut and Chulalonghorn, democratic leader Pridi Banomyong, and the artist’s own grandmother whose husband was martyred to the cause of Thai royalty- are portrayed weeping tears of blood –metaphorically in the case of the grandmother- for their country and her weak and deluded citizens. Legible and straight-forward in its message, the sequence was the show’s most personally engaged and thus created an easy rapport with its audience. Further than its more obvious reflection on the consequences of history however, the work, in illustrating two much revered Siamese kings shedding tears like commoners, also provided a subversive if oblique critique of the royal institution. By suggesting the kings’ humanity and thus fallibility, the artist effectively rebukes the Thai people for their contemporary deification of the monarchy, thus pinning the responsibility for the nation’s problems squarely on its people.

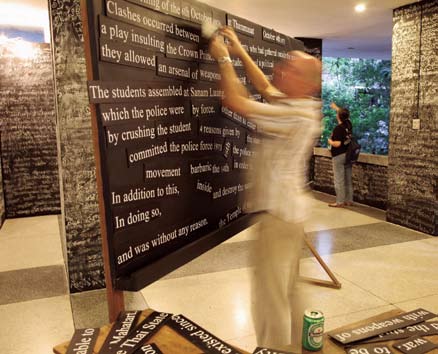

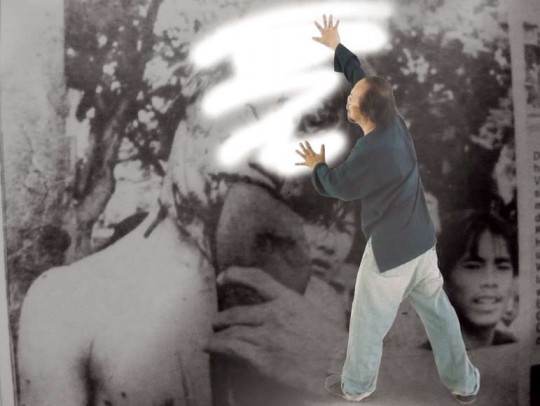

A second group exhibition mounted by the same trio along with Vasan Sitthiket was put up at the Pridi Banomyong Institute in 2008. Focusing solely on the 1976 October 6 massacre, the show, titled “Flashback ‘76”, saw the majority of artists paying tribute to the young victims whom they evoked with a variety of media. Ing K and Manit Sriwanichpoom took blood-red as their leit-motif, the first portraying both perpetrators and victims in monochrome red-spattered red watercolor, the second developing photographs of the murdered victims in a bath of blood-red revealing solution. Vasan Sitthiket employed video, reproducing the now well-known press photographs of the period in huge scale with the artist filmed manically, desperately attempting to blot out the scenes of horror with his flaying arms. Presenting two possible and not mutually exclusive readings, Sitthiket’s ‘Delete Our History, Now!’ can be received as a darkly pessimistic work that references contemporary society’s knowing refusal to remember and learn from history, and its willing collusion with the state in the distortion of the past. A chink of hope emerges however, if one interprets the artist’s frantic gestures as belonging to one who seeks to reverse the course of history rather than delete it after the fact. Purging and cleansing Thailand’s sins against her own people, Vasan Sitthiket also proposes a better future for those willing to acknowledge and understand the past.

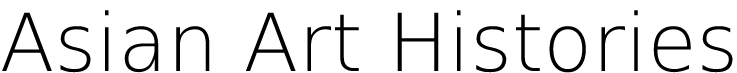

Sutee Kunavichayanont, for his part, produced a text-based work that used bitter-tinged irony to remind Thais of their responsibility for past and future history-altering choices. Including a reference to the cynical right-wing monk who at the time of the massacre famously proclaimed the killing Communists not to be a sin, the larger part of the installation reverted to the class-room setting of earlier work with its subversion of he officially sanctioned version of history. This part of ‘Selective History / Memory’, interactive, called upon viewers to arrange key phrases set out on a school-room black-board. The words history, by choice, to memorize, choosing to remember, intentional and forget could be shifted around the board at will, so forcefully prompting members of the public to write their own version of history and remember their personal involvement in its creation. Underscoring the ease and convenience with which the past can be subjectified, and conversely the weakness, moral poverty and larger dangers associated with the obfuscation of objective truth, Sutee Kunavichayanont’s ‘Selective History / Memory’ was an insidiously disturbing piece that worked its way under the skin of viewers’ consciousness well after they had left the gallery.

History and memory have also been a means of dissecting more localized Thai issues.

‘Peoples’ Constitution’ of 2000 is perhaps Vasan’s most literal and idealistic political work, proposing to re-make existing history. A critique of Thai democratic institutions as set out in the country’s reformist constitution of 1997 –since replaced by far more illiberal post 2006-coup measures-, Sitthiket’s version provides the artist’s own rule of law. His is a socialist/anarchist manifesto that in deliberately countering the errors of history, proposes a new and more equitable future for the Thai people.

20th century industrialization, historically irreversible and altering Thai rural life for ever, is a another central theme for Sitthiket. Various series examine the topic, amongst the most evocative ‘Committing Suicide Culture: the only way of Thai farmers escape debt’ from the seminal 1995 exhibition “I Love Thai Culture” at Bangkok’s National Gallery. A graphic commentary on the plight of Thai farmers, victims of forcible government land re-possession, the installation shows a row of cut-out plywood farmers dangling by the neck from nooses fixed to a metal frame painted the colours of Thailand. Frightening in the potency of its cartoon-evocation of suicide, yet of commanding formal elegance, the piece takes the plight of the Thai farmer from its parochial setting into a universal one.

Numerous Other works and series by the same four artists have, over the years, reverted to themes of history and memory, some reaching beyond the confines of Thailand. Incorporating the Pink Man icon and marking events that have influenced the course of regional history is Manit Sriwanichpoom’s ‘The Pink Man in Paradise’ series. Made in the months following the 2002 Bali bomb blast that killed hundreds on the Indonesian resort island, the group of Balinese landscapes and temple vistas shot in black and white and punctuated by Pink-Man & shopping cart is visually arresting in its juxtaposition of the luridly vulgar quintessential consumer Pink-Man against the backdrop of Bali’s peaceful idyll. Psychologically too the series is potent, Pink-Man an allusive metaphor for the intrusion of modern sectarianisms and their random violence in all our lives. Again, like ‘Horror in Pink’ Sriwanichpoom’s Bali series, more than highlighting a specific instance of murderous violence, speaks of history’s wider, universally-relevant connotations.

Vasan’s 2001 50 portrait series ’We come from the same way’ addresses history in a global context. Philosophical in bent, the sequence is amongst Sitthiket’s most conceptually original and graphically splendid. Illustrating the birth of both Thai and world historical icons, the latter are shown emerging from between an anonymous woman’s splayed legs. Referencing universal concepts of innocence and evil, choice, and self-determination, the subtly provocative work challenges the assumption that good and evil are distributed fortuitously while conversely underlining man’s responsibility for his own actions and destiny, the raw ingredients of history. Irony and suggestion underpin the work, playing on our knowledge of the icons of culture, faith and power who have changed lives manipulating good and evil –Hitler, Stalin, Idi Amin, Jesus Christ, Franz Kafka, Joseph Beuys, Mahatma Gandhi, Pridi Banomyong, as well as the artist himself-, while hinting at the possibility of innocence through a re-routing of history and choice. Speaking equally to Thai and non-Thai, atheist and believer ‘We come from the same way’ underscores the artist’s belief in a common future for which all must work together for the plural good.

Sutee Kunavichayanont, always cerebral in approach, has often set his exploration of Thai issues in a wider cultural and historical context. Siamese Breath (and related pieces) of 2000 is an example of one such far-reaching work. Executed in silicone and an extension of the artist’s ‘Depletion-Inflation’ series of the late 1990’s, the installations represent a pair of seated, standing or reclining inflatable figures to whom the artist gives identical features but molds one in white, the other in yellow. Alluding to the famous conjoined Siamese twins Chang and Eng who wowed American carnival audiences over a century ago with their deformity, the piece, though never overtly didactic, raises several key cultural issues seen through the lens of history: the history of Siam’s foreign-perceived exotic aura is investigated via the twins, who contributed to publicizing Thailand –and her exoticism- in 19th century America; giving the twins Eastern and Western identities (yellow and white), the artist ponders the historic polarization and interdependence of the two civilizations and their cultures, leading the viewer to conclude that one and the other are never absolutely opposed or exclusive. Further, exploiting the interactive formal device of ‘Depletion-Inflation’ that the artist has over the years utilized to express so many ideas, Kunavichayanont’s piece, varying in stature according to levels of the white and yellow figures’ inflation, mirrors the altering balance of East-West power, influence and international stature over the centuries. Finally, putting the state of inflation or depletion of his two emblematic figures in the hands of the breath-donating audience, Kunavichayanont reinforces the notion that we are all owners of, actors in, and responsible for, our shared and intertwined histories and destinies.

Amongst the most recent works of visual art probing Thai history is the 3 hour 42 minute 2008 film Citizen Juling made by cinematographer, poet and painter Ing K., Manit Swriwanichpoom, and progressive ex-senator and civil rights defender Kraisak Choonhavan. Shown on the international festival circuit, the film portrays Thailand as her people grapple with the implications of sectarian troubles in the South. Thai colonial history, the monarchy, nationalism, and nascent democratic institutions are subjects probed more or less directly by this deeply humanistic cinematographic work about the fate of a Buddhist school teacher in a coma after being beaten by Muslim women. Neither judgmental nor sentimental, Citizen Juling elucidates Thai contemporary history in the making with finesse.

Though on the margins of Thailand’s artistic mainstream the small group of artists consistently investigating the nation’s history and collective memory is far from alone in wider Southeast Asia. The socially and politically engaged contemporary practices of the region, at their best neither literal nor earnest, are often as visually arresting as they are committed to meaning. Refreshingly unfashionable on the commercial circuit, this art harnessing concept and visual power to ideals, however challenging, is the stuff of regional art-history.

For further reading, please see:

National Identity and its Defenders- Thailand Today,

Craig Reynolds Ed., Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai, 2002

Corruption & Democracy in Thailand, Pasuk

Phongpaichit and Sungsidh Piriyarangsan, Silkworm

Books, Chiang Mai, 1996

Democracy and National Identity in Thailand, Michael

Kelly Connors, Nias Press, Copenhagen, 2008

Jungle Book- Thailand’s Politics, Moral Panic, and

Plunder, 1996-2008, Chang Noi, Silkworkm Books,

Chiang Mai, 2009

The Politics of Ruins and the Business of Nostalgia,

Maurizio Peliggi, White Lotus, Bangkok, 2002

Iola Lenzi is a Singapore-based researcher and critic specialising in Southeast Asian contemporary art. She takes a synthetic view of regional practice, her texts and exhibitions seeking to compare regional themes, expressive languages, and conceptual approaches. She has curated exhibitions in Singapore, Jakarta, Bangkok and Kuala Lumpur focusing on art commenting Southeast Asia’s socio-political landscape of the last 15 years. Lenzi is the Singapore correspondent for Asian Art newspaper, London, a contributing editor to C-ARTS Jakarta/Singapore, as well as a frequent contributor to other international art publications. She curated the recent Singapore Art Museum show Negotiating Home, History and Nation: two decades of contemporary art in Southeast Asia 1991-2011, is a founding member of AICA Singapore, and the author of two books. She is currently teaching in the MA Asian Art Histories programme at LASALLE College of the Arts.

This article was first published in the November/December 2009 issue of C-Arts