by Abdul Hafiiz Bin Abdul Karim

Art is our last voice of freedom as it is the extension of our sense of self. It allows us to make our presence visible and to establish our own version of the truth. For the artists in The Artist’s Voice, this statement rings true in a collection of electrifying, emotional and expressive works. Held at the Parkview Museum, an art space dedicated to showcase contemporary art, this major international exhibition was curated by one of European’s foremost curators and art historian, Lorand Hegyi. Hegyi definitely had an ambitious but daunting task to identify and present the artistic inner voice of artists without facing the risk of essentialising it. By showcasing works by 34 contemporary artists from 16 countries, Hegyi managed to connect multiple perspectives of realities that explore sensitive, yet universal issues within the theme of the artist’s voice.

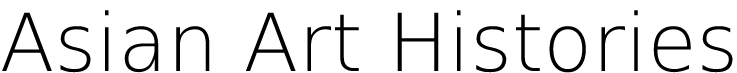

The exhibition title is clear for visitors to expect socially engaging works that deals with self-expression of culturally specific issues that the artists attempt to communicate. Some of the strongest works deal distinctively about the context from which they came from while taking the viewers knee-deep in raw emotions. Bill Viola’s Remembrance video installation is possibly the most successful and emotional work in the exhibition (fig. 1). Viewers who enter the dark room can expect a silent video of a lady’s unfolding expressions in slow-motion at the end of the room. No other pretentious gimmicks. The video intimately pulls viewers in to watch an oscillation of intense emotions slowed down to make visible the subtle changes of expression. The video reflects a grieving New York during the aftermath of the September 11 attacks. It not only resonates with victims of the attacks but also anyone who has experienced loss or death. Sitting through the entire 16 minutes video, viewers are transported into a quiet and contemplative place deep within them where a nakedness between the viewer and the video emerges. Life and art merges in this work to produce an experience that is honest, pure, and direct.

Figure 2. Roberto Barni, Clandestini, 2008, bronze sculpture,

Cage: 220 x 220 x 220 cm/Men: 1758 x 65 x 75 cm.

Another work that emboies the curatorial theme is not located in the exhibition space, but appropriately showcased outside Parkview Square. Roberto Barni’s Clandestini is a bronze sculpture of a cage with four anonymous male figures standing around it looking into the empty space. However, without the aid of wall text, viewers may not know that the work was created right when Italy faced immigration from North Africa. More importantly, Clandestini (fig. 2) is a successful work due to its timeless and universal quality. It comments on the guilt human beings face when they experience freedom. Viewers who walk around the cage would be reminded of the conformism and convention that they are still a part of even though they are in the state of freedom.

Figure 3. Maurizio Nannucci, New Times for Other Ideas/New Ideas for Other Times, 2017, neon light installation.

Tucked away at the edge of the gallery space, Maurizio Nannucci’s neon light installation hardly went unnoticed. The neon-lit words New Times for Other Ideas and New Ideas for Other Times is reflective of Nannucci’s body of work as he explores light, colour, and language to re-aestheticise the models of communication in contemporary society (fig. 3). This work naturally became an Instagram-worthy spot, where visitors set up their cameras and snap a selfie or two. The image produced by the neon-lit words transcends representation and becomes a mental image or a virtual one that is shared and consumed by other people. In communicating short but powerful messages through the medium of neon, Nannucci’s work has entered into the realm of advertising. One cannot deny that this visually arresting piece prompts us to question the old assumptions of an artist’s visual language.

What seems to be an exhibition that give importance to the artist’s voice, appears to be one that glorifies the European male voice. It is unfortunately ironic that the curatorial concept talks about the plurality of perspectives in contemporary discourse; the decentered voice which claims to uncover realities that often remain unrecognised in everyday life. In actuality, the exhibition still presents a dominant voice directed towards a superior European collective. It still fails to recognise the voices of the Other, which therefore, dampens its attempt to challenge the dominant reality. This is not surprising coming from Hegyi who specialises in modern and contemporary art in Central and East Europe. However, the dominant European male voice that is rooted in the exhibition should not obscure visitors’ insights offered to open up their understanding on the multiple experiences and identities surrounding a particular work by a female artist or an artist of colour.

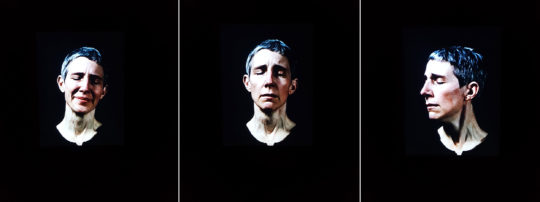

While there is a dominant European male voice in the exhibition, Hegyi made attempts to represent works by minority artists. To see watercolour and ink works from Cameroon artist Berthélémy Toguo is refreshing as the fluidity of his brushstrokes relates to the natural purity that is important to him. In Green Forest, Toguo utilises traditional cultural symbols of African rituals to speak about the recent tragedies in his country (fig. 4). The body, pierced with nails, bleeds in a darker shade of green indicating that the fate of humankind and nature are strongly linked. Any pain inflicted upon nature will ultimately affect humankind. While the issue of exhibiting only one African work is crossing the line of essentialising notions of “Africanness”, Toguo’s works on human being’s relationship with nature more importantly connects his concerns about his country, and towards all of humanity on Earth.

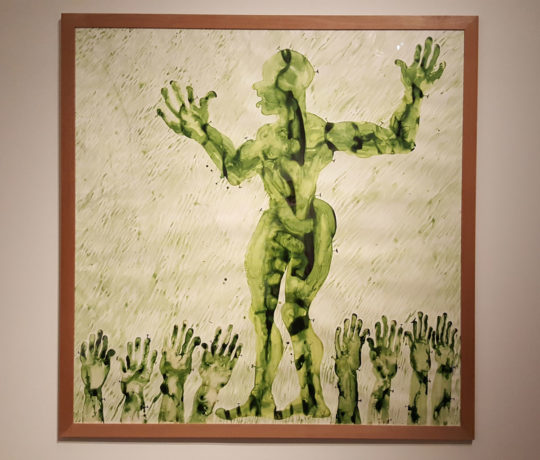

Another group of non-Western artists are four Asian artists from Korea and China. Their works are also worth noting as their styles vary from one that stayed true to their Asian heritage to expressing issues that relates to a wider audience. Wang Luyan, a member of the contemporary group Stars, produces provocative works like W Fire At Both Ends Automatic Handgun that is infused with a critical take on the materialistic society and human nature such as death, destruction and suicide. Liu Xiaodong, a Chinese artist who delivers an Asian perspective on Europe’s migrant crisis in powerful and poignant painting titled Refugee 1. Chun Sungmyung, a Korean artist who is known for her striking and haunting sculptures that resembles him, explores the darkest aspects of human nature such as those in Swallowing The Shadow. Lastly, in Minguo Landscape by Qiu Anxiong, a Chinese artist, uses animation to retain the formal quality of Chinese landscape painting (fig. 5). While it is undeniable that the choice of medium brings new life to this traditional art form, there is nothing particularly groundbreaking about this visually arresting piece besides preserving its cultural heritage and revealing stories of the establishment of the Republic of China through moving images.

It is a real pity for a major international exhibition to showcase works by four female solo artists out of the 34 contemporary artists. Having publicised the exhibition with internationally renowned artist Marina Abramovic as the featured artist in the key visuals, one would expect more female representation in the exhibition. Pietà is a still photograph taken from a live performance by Abramovic where she gently carries the body of her boyfriend in her arms (fig. 6). The red and white clothing donned is attributed to Chinese mythology where the universe is considered to be a product of a drop of female blood and sperm respectively; a balance of womanhood and manhood. Yet, this balance is not reflected in the male to female ratio of artists in the exhibition. The exhibition once again falls into the dangers of essentialising the woman’s voice. While Abramovic does not regard herself as a feminist, to do so while making art would only reinforce the traditional binaries of gender. Ultimately, her works deals with subverting the idealisation and objectification of the female body as she uses her own body in her performances.

One aspect in which the exhibition lacks is the inaccessibility to locate the wall texts of the works as it requires contextual information to be accurately understood. Some wall texts are poorly lit as visitors turned on their camera flashlight to read. Some wall texts are placed too far away from the artworks. These issues disrupt the visitor experience in reading the texts that are undeniable easy to comprehend.

The Artist’s Voice reaffirms the importance of the role of the artist in articulating the human state of existence and passes the baton to visitors who have an urgent responsibility to give a voice to the oppressed or silenced wherever they may be.

This exhibition ran from 17th November 2017 to 17th March 2018 at Parkview Museum.