by Luke Chua

The first international exhibition of the National Gallery Singapore (NGS), titled Reframing Modernism, rides on the huge waves generated by the opening of the Gallery as one of the largest visual art museums in the region in November 2015. The exhibition aim is impressive: to reframe the understanding of modernism which has been built by decades of art historical scholarship. While laudable and certainly a worthwhile effort, the result may have fallen slightly short of expectations.

This exhibition, organised in collaboration with the Centre Pompidou, Paris, presents a selection of more than 200 works from NGS and loans from the Centre Pompidou and around the world. It seeks to tell a new story of modernism in art, specifically painting, through Southeast Asian eyes. The narrative takes place over three galleries across an approximate area of 1,960 square metres and is told by the curatorial team of five members: director Eugene Tan, senior curator Lisa Horikawa and curator Phoebe Scott from NGS; as well as deputy director Catherine David and curator Nicolas Liucci-Goutnikov from the Musée National d’Art Moderne of the Centre Pompidou. However, the enterprise to “reframe” something as big as modernism may be too ambitious for a show that is better packaged as a slice of global modernism.

A key feature of this exhibition is the juxtaposition of Southeast Asian artists with their European counterparts in order to illuminate similar concerns across the two regions and how these are manifested on the canvas. The story is not of derivation but of connections. This sets the show apart from other surveys of modern art which are structured chronologically or around artistic styles such as Cubism or Abstract Expressionism.

The starting point is Southeast Asia, with the NGS curators first proposing a list of artists from the region and the Centre Pompidou responding by selecting artists from their collection. Hence, the focus is on creating conversations between individual artists and the exhibition functions as a collage of mini solo exhibitions in the absence of an overarching theme. On average, five works per artist are shown but a handful of artists, such as Spanish artist Pablo Picasso and Filipino painter Victorio C. Edades, are represented by single works. Given the artist-centric focus, one wonders if a single work can represent an artist’s practice, especially for artists as eclectic as Picasso. Yet, practical constraints in loaning works from other museums may have prevented a more comprehensive showing.

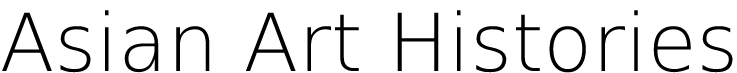

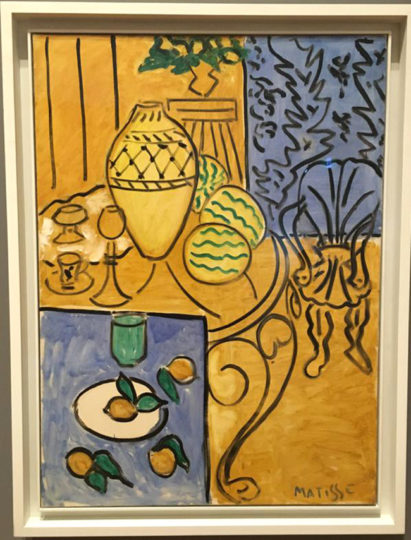

The show starts promisingly with single works of two artists. When first entering the gallery, one is faced with French artist Henri Matisse’s Interior in Yellow and Blue (fig. 1) and the massive The Fairies (fig. 2) by Vietnamese artist Nguyen Gia Tri facing each other in dialogue. Hailing from different regions, both artists are experimenters in composition and colour in two different mediums: oil on canvas and lacquer respectively. Matisse uses large blocks of plain colour to flatten the composition in his canvas while Tri rubs back successive lacquer coatings to reveal colour blocks. The use of bold outlines to delineate spaces can also be seen in both works. Despite these similarities, each piece retains its distinctiveness. As opening pieces of this exhibition, they give the viewer a good sense of what the curators are aiming to achieve.

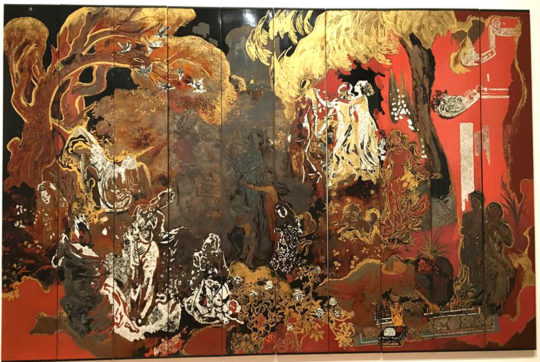

Other artists represented by a body of works are also placed within close proximity to artists from a different region who share similar concerns. Some suggested ways of connecting the artists are given in keywords printed beneath gallery layouts on the walls. Across the three galleries, a range of 39 keywords, such as cosmopolitan, nativism, colour, line, and transcendence are given (fig. 3). However, these words are not always prominently featured in the wall texts, which remain artist-centric and broadly biographical in nature. Some of the keywords are also abstract and convey little interpretive meaning without explication.

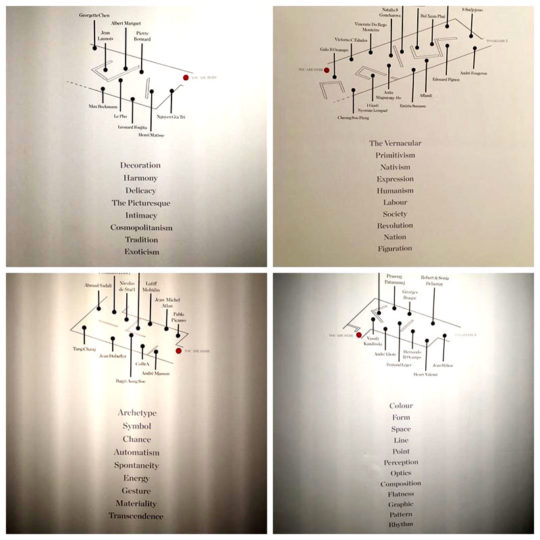

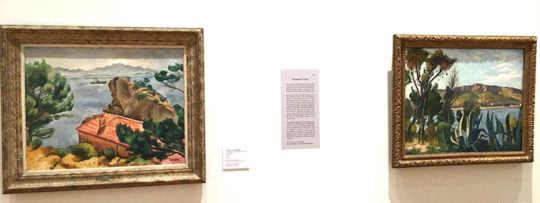

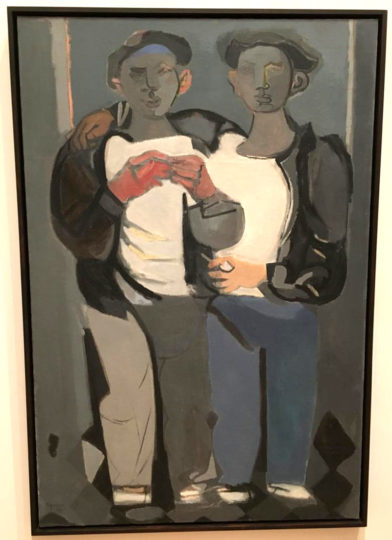

18 of these keywords are found in the first gallery, the largest among the three and featuring mostly figurative works. While connections in subject matter can be detected easily between works such as Singapore artist Georgette Chen’s and French painter Albert Marquet’s landscapes (fig. 4), they remain elusive in other clusters. For example, Indonesian S Sudjojono (fig. 5) and French artist Edouard Pignon (fig. 6) deal with socio-political issues and are placed together but connections between subject matter are not immediately apparent from the works.

Figure 5.

S Sudjojono. Seko, Prambanan (The Guard, Prambanan). 1968. Oil on canvas. Museum of Fine Arts and Ceramics, Jakarta.

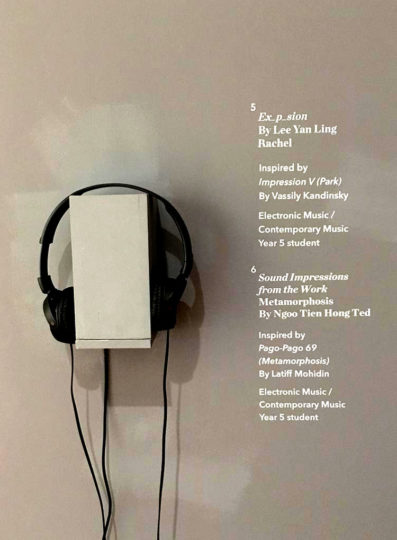

As one meanders through the first gallery, the exhibition loses the strong start given by the Matisse-Tri pairing. It does not help that the space of this gallery is disrupted by partitions erected at odd angles (fig. 7), further bewildering the visitor who is trying to make sense of the works. Additional features such as music stations and book corners are also incongruously located between the first and second galleries rather than at the end of the exhibition, thereby disrupting the exhibition connectivity and flow. The music stations feature compositions inspired by the artworks (fig. 8) but some works can only be seen when one proceeds further in the gallery. While the connection between music and art is intriguing, especially for artists such as Vassily Kandinsky from Russia, this link would have been more apparent if images of the artworks are available at the stations, or if the stations are located where the actual art pieces can be seen.

In this exhibition, not all artists are considered in relation to others. Of noteworthy mentions in the second gallery are the surveys of Kandinsky and French painter Jean Hélion. Kandinsky’s selection is placed at the start of the second gallery and is well curated with a range of his early figurative works and later abstract works. This fits well with the curatorial intent to focus on the development of individual artists. At the end of the gallery, one sees a reverse journey for Hélion, who is represented by works charting his journey in the opposite direction from abstraction to figuration. While the intention is to place European artists alongside Southeast Asian artists, a Kandinsky-Hélion pairing would have made for a fascinating comparison (fig. 9).

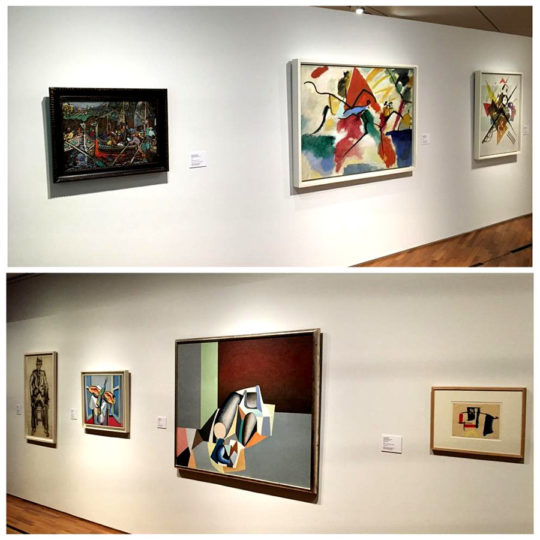

Figure 9.

(top) Vassily Kandinsky’s progression from figuration to abstraction from left to right.

(bottom) Jean Hélion’s progression from abstraction to figuration from right to left.

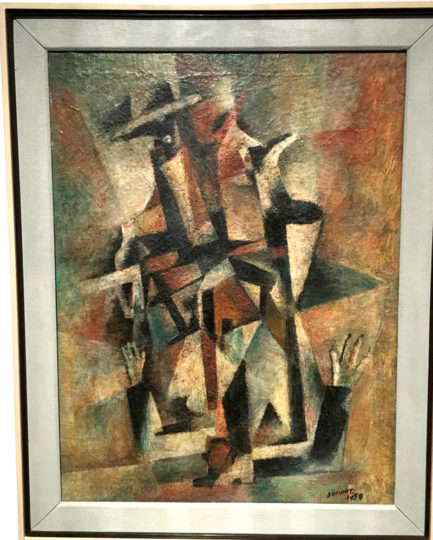

The connections in the second and third galleries are clearer as they are generally visual in nature. For instance, the visual similarity between the cubist works of Thai artist Sompot Upa-In and French painter Georges Braque are obvious. Employing similar techniques of fragmenting the pictorial object to depict multiple perspectival views simultaneously, Sompot’s Politician (fig. 10) bears much visual resemblance with Braque’s works (fig. 11) and could have been mistaken to be his work by the unknowing viewer.

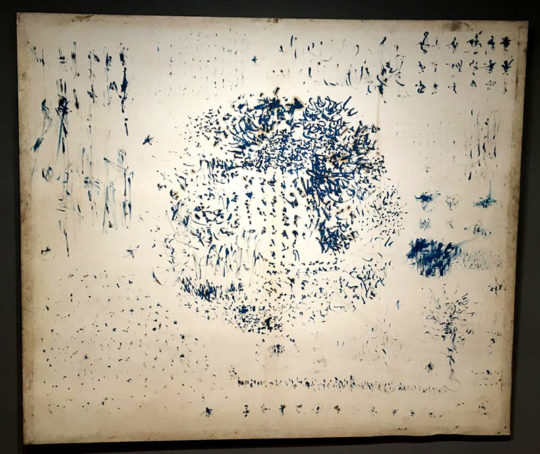

In these two galleries, the visual coherence across the varying degrees of abstraction creates a sense that one is visiting a conventional exhibition on Western modern art. Yet works such as the calligraphy-inspired paintings by Thai artist Tang Chang (fig. 12) remind us that this is also an exhibition of Southeast Asian artists who, while working in modern artistic styles, are influenced by their Asian backgrounds. In terms of curatorial intent, these two galleries seem to have achieved better results in creating coherent spaces occupied by artists from different regions exploring similar stylistic innovations in painting.

The strength of the second and third galleries begs the question of whether an exhibition on modern art would inevitably fall back to discussions of artistic styles. When modern art is mentioned, associations of stylistic innovations and schools of artistic movements are typically evoked. This exhibition has attempted to veer the discussion in a different direction by dedicating the first gallery, which makes up half of the entire exhibition, to other shared concerns such as humanism, exoticism and tradition. Nevertheless, the second and third galleries come across as the more impactful spaces with deeper examinations of the extent to which artists from different regions converge or diverge in their stylistic explorations. In addition, the diverse histories and complex socio-political situations of the different regions do not allow for easy associations among artists in the first gallery.

For an exhibition seeking to reframe modernism, giants such as Claude Monet, Édouard Manet and Vincent van Gogh are also conspicuously absent. Granted that this is not meant to be a comprehensive survey of modernism, the exhibition could have been contextualised within a larger discussion of global modernism instead of purporting to reframe modernism. This contextualisation, which could take the form of a brief overview of prominent artists and major artistic movements, is missing.

However, some effort has been taken to initiate discussions through curatorial roundtables, panel discussions and art talks which provide some grounding in ideas of modernism. A more lasting and deeper critical engagement could have been achieved with scholarly essays or reviews compiled in catalogues but regrettably, while souvenirs such as postcards and posters are available at the museum shop, there are no books published specifically for this exhibition at the time of writing.

Despite the gaps in coherence and critical engagement, Reframing Modernism is a commendable exhibition which attempts to address the diversity of modernist art practice in Southeast Asia, in line with NGS’s objective to be a leading museum of modern art in the region. The harking back and comparison to Western modernism paradoxically reinforces its historical precedence and influence but this is a perennial consideration which will emerge in any survey of modern art. It is no easy feat to tackle issues of modernism amidst the heterogeneous histories of the region where artistic styles do not necessarily emerge in a linear format. As a starting point, this exhibition provides a good primer on Southeast Asian modern art but its significance can only be assessed after sustained and continued engagement to place Southeast Asian modernism in the right “frame” of mind.

Luke Chua is currently a student of the MA Asian Art Histories Programme. The article was originally done as part of an exhibition review assignment. All images are taken by the author.

The exhibition runs till 17th july 2016 at the National Gallery Singapore