by Derelyn Chua –

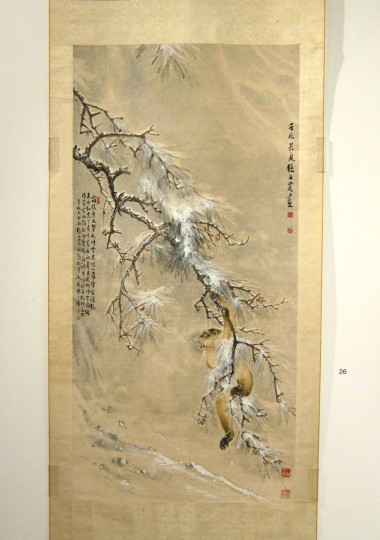

Between Here and Nanyang is an exhibition in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Marco Hsu’s A Brief History of Malayan Art and is intended to coincide with Singapore’s fifty years of independence in 2015. The text seeks to break away from the view that Malaya is a cultural desert, to highlight the vibrancy of Malayan art and define the Malayan cultural identity.1 While the exhibition is meant to mirror Hsu’s text with minimal curatorial interference, it is worthy to note instances where the curators had actually intervened. This review examines the exhibition’s representation of Malayan heritage to highlight that there is unsatisfactory resolution of historical complexities.

From the outset, it is important to acknowledge the circumstances in which Hsu was writing his book. Hence, this review is not a critical examination of Hsu’s text but rather, of the exhibition that purports to have minimal curatorial intervention in promoting a particular heritage in present-day Singapore. The exhibition mirrors Hsu’s text and frames Malayan art in a chronological perspective. The exhibition’s first panel introduces the overarching theme by extracting Hsu’s premise for his text–the search for a cultural identity of Malaya. Tied to the overarching theme, the second premise centres on the dynamism of Malaya, which was able to respond to both internal and external forces through cultural assimilation.

Hsu argues that Malaya has never been a cultural desert, even in pre-historic times. Instead, Malaya is presented as a melting pot of cultural variety, with the common bond of colonialism providing Malayan artists with a universal language, to create its own shared heritage and cultural identity, despite the heterogeneity of the Malayan immigrant population.

The first section of the exhibition displays Chinese scroll paintings and early colonial picturesque landscapes of Malaya, to exemplify the movement of people into the region. It is used as a contrast to the next section of the gallery (the practices of the artists in the 1950s) to bring out the notion of cultural assimilation more strongly.

Early travellers, like Chang Tan Nung (Fig 3) are either still concerned with the motherland or, like Charles Dyce (Fig 2), who had minimal interest in painting the local population because of his lack of interaction with them, and thus knew little about their lives.2

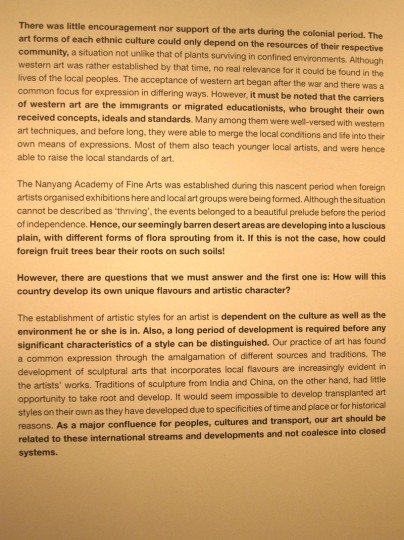

Finally, the exhibition concludes with four panels containing excerpts of Hsu’s text, which accentuates the importance of the artists he has selected.

It is pertinent that the curators have chosen to stress on certain sentences, which has the effect of putting forward the agenda of the exhibition–that the artists are indispensable proponents and upholders of the Malayan artistic traditions and dynamic Malayan society, as well as creators of the Malayan cultural identity.

It is easily discernible that the curators have the power to make Hsu’s text relevant for modern-day Singapore, in the furtherance of nation-building. This is particularly relevant for institutional curators, whose role is often delineated by the administration to endorse a “national imaginary”.3

Curators are subjects of nation states and as such they work under the constraints and possibilities of this structure. The latter puts pressure on curators at various levels: to abide by cultural identities (social, cultural, religious), to operate within limited resources of education and infrastructure, to support the state in its mandate of cohesion and integration.4

It will be readily seen that there is a lack of critique of Hsu’s text in the exhibition’s discourse because the various functions of the curators have been usurped by having to weave the Malayan cultural heritage to suit the Singapore context. As the museum curator Chang Yueh Siang said in an interview:

Before the Malayanisation movement of the 1950s, artists and art historians didn’t think of themselves as Singaporean or Malayan artists. It’s only when you have this notion of nation building that people began to think of themselves as local, Malayan artists.5

Thus, there is a “critical nostalgia for a useful, usable past”,6 in which the paintings have become accomplices to the state, as a source of identity. June Yap rightly points out:

The manner in which the commercial, cultural and political situations influence and affect the ability for curatorial practice to flourish is similarly felt in Singapore, where curating is largely subsumed under the practicalities of exhibition organisation and its poetic gestures too subtle to be heard above a bureaucratic clamour for spectacle. As Flores also notes, though in relation to how institutional curation is also challenged by the vast scope it is supposed to represent, curating in Southeast Asia is often rendered almost tactical.7

Yap suggests that curators such as Yueh Sian have been “sidetracked into conformity and collusion with local oligarchies”,8 where art is used in the production of national identities. For example, through the layout of the gallery (Fig 5), the visitors follow a chronology of artistic developments in Malaya, with early artists contrasted against the first-generation artists, and the latter being juxtaposed against second-generation artists (Fig 6 and 7).

The contrast is meant to bring to our attention, the Malayanisation of Chinese paintings through the shift in subject-matter, in Lim Hak Tai’s Prunus (Fig. 6) to Pounding Rice by Lai Foong Mui(Fig. 7). Furthermore, there is an emphasis on the 1952 historical field trip as a search for a Malayan visual expression.

Here, the curators suggest that Singaporean art hitherto was not characterised by “ritualistic, experiential and decorative elements”,9 and consequently, the trip was a turning point in artistic expressions, indicating the emergence of the Malayan cultural identity. Therefore, it is arguable that the curators, in choosing to place emphasis on the differences in art practices, have actively promoted particular artists as being quintessential Malayan artists, and in turn, contributes to an existing discourse of a Singaporean cultural identity.

Furthermore, even though the curators have claimed non-intervention in the historical show, by including Michael Lee’s contemporary glass installations, the curators have effectively attempted to interpret Hsu’s text.

The glass installations in Fig. 9 and 10 are venues where art exhibitions were held, and when seen at eye-level, create depth that contributes to the vibrancy of the venues. This has the effect of showing the popularity of the art exhibitions and to further enhance the reputations of the artists Hsu has selected. This intervention may also be perceived as a method of how Hsu’s Malayan history has been re-interpreted for present-day Singapore because the curators have asserted that history is not “glass-case in the past”,10 and nation-building is a continuous project. It appears that the curators have limited the use of art to “the production of identities for the national and the nation state; and its appropriation as an economic and cultural good… as part of the mythology of nationalism, with curators and artists, for instance, party to propagating official images of the nation and monuments”.11 It is clear that the curators have not seen art as indispensable in the creative expression of a critique against a ‘hegemonic imaginary’.12

In conclusion, the exhibition offers a discourse of a shared heritage through a culturally rich and diverse Malaya that was able to adopt and adapt to external influences. Concurrently, the exhibition functions as a vehicle to propagate particular values of assimilation to sustain a consciousness of a common identity in present-day Singapore. This paper has also attempted to explore the difficulties institutional curators may face, especially in light of an exhibition that has a clear agenda of celebrating fifty years of nationhood. The curators have placed emphasis on the changing art practices to indicate the Malayanisation of art and, in doing so, have legitimised and uplifted the nation-building project. While it is acknowledged that Malaya in the 1950s was indeed vibrant, the curators have failed to satisfactorily resolve the complexities in Malayan history that has been purposefully avoided by Hsu. Thus, it is arguable that because of the curators’ lack of critical assessment of Hsu’s discourse, the exhibition’s purpose may have been hindered.

Derelyn Chua is currently a student of the MA Asian Art Histories Programme. The exhibition runs till 2015 at the NUS Museum

Bibliography

Books

Aplin, Graeme. Heritage: Identification, Conservation and Management. South Melbourne:

Oxford University Press, 2002.

Choay, Francoise. The invention of the historic monument. Translated by Lauren M. O’Connell.

New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Flores, Patrick D. Past Peripheral: Curation in Southeast Asia. Singapore: NUS Museum,

National University of Singapore.

Hsu, Marco. A Brief History of Malayan Art. Translated by Lai Chee Kien. Singapore:

Humanities Press, 1999.

Jegadeva, Anurendra. This is Where We Live –The Ongoing Search for a National

Narrative in Narrative. Edited by Nur Hanim Khairuddin and Beverly Yong. Kuala Lumpur: RogueArt, 2012.

Nur Hanim Khairuddin and Yong, Beverly. Part I: The Journey from the Rural to the

Urban, and the Building of a Nation. Edited by Nur Hanim Khairuddin and Beverly Yong. Kuala Lumpur: RogueArt, 2012.

Sabapathy, T K. In Conversation: Tang Mun Kit & T K Sabapathy. Edited by Tang Mun

Kit. Singapore: Tang Mun Kit, 2013.

Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism. London: Random House, 1993.

Sullivan, Michael. Art and Artists of Twentieth-century China. Berkeley, California: University

of California Press, 1996.

Yeoh, Brenda. Hidden Views, Humanised Landscapes in Colonial Singapore. Edited by

Irene Lim. Singapore: NUS Museums, National University of Singapore, 2004.

Journals

Brenson, Michael. “The Curator’s Moment,” Art Journal 57, no. 4 (Winter 1998): 16-27.

Izmer Ahmad. “Tracing the Mark of Circumcision in Modern Malay/sian Art.” Ph.D

diss. University of Victoria, 2008.

Renfrew, Magnus. “What is the new in curating today.” in Who Cares: 16 Essays on

Curating in Asia (Hong Kong: Studio Bibliotheque, 2010. 141-144.

Internet

Geringer Art Ltd, Mohammed Hoessein Enas (Javanese, 1924-1995).

<http://www.geringerart.com/bios/enas.html> (Date of access 12 September 2013).

Huang Lijie, “A long look back at Malayan art”.Huang Lijie, “A long look back at

Malayan art,” The Straits Times Community. 31 August 2013, <http://origin-stcommunities.straitstimes.com/show/2013/08/31/long-look-back-malayan-art> (Date of access: 5 September 2013>.

Kian Chow, Kwok. “Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts and the Beginnings of the

‘Nanyang School’,” Channels and Confluences, The Literature, Culture and Society of Singapore in the Postcolonial Web. <http://www.postcolonialweb.org/singapore/arts/painters/channel/7.html> (Date of access: 16 September 2013).

“Social Realist Trends: Woodcut Movement, Equator Art Society,” Channels

and Confluences, The Literature, Culture and Society of Singapore in the Postcolonial Web. <http://www.postcolonialweb.org/singapore/arts/painters/channel/15.html> (Date of access: 14 September 2013).

“Sino-Japanese War,” Channels and Confluences, The Literature, Culture and

Society of Singapore in the Postcolonial Web. <http://www.postcolonialweb.org/singapore/arts/painters/channel/8.html> (Date of access 12 September 2013).

“The Bali Field Trip: Liu Kang, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi and

Cheong Soo Pieng,” Channels and Confluences, The Literature, Culture and Society of Singapore in the Postcolonial Web Channels and Confluences <http://www.postcolonialweb.org/singapore/arts/painters/channel/12.html> (Date of access: 15 September 2013).

Ministry of Home Affairs. “Remaking Singapore –Changing Mindsets,” Prime Minister’s

National Day Rally 2002 Speech, 18 August 2002, <http://www.mha.gov.sg/news_details.aspx?nid=MjA4-OoIshwLg%2Bn4%3D> (Date of access: 15 September 2013).

Yap, June. “Perspectives: Curatorial connections, Southeast Asia: Three panels, two

books,” Asian Art Archives. April 2009. <http://www.aaa.org.hk/Diaaalogue/Details/636 – diaaalogue_hidden_menu> (Date of access 11 September 2013).

Yeo, Alicia, and Balagopal, Roberta. “The Nanyang Style”, Singapore Infopedia: An

electronic encyclopedia on Singapore’s history, culture, people and events, <http://infopedia.nl.sg/articles/SIP_1626_2009-12-31.html> (Date of access: 13 September 2013).

- T K Sabapathy, Foreword to Marco Hsu, A Brief History of Malayan Art, trans. Lai Chee Kien (Singapore: Humanities Press, 1999), vii. ↩

- Brenda Yeoh, “Hidden Views, Humanised Landscapes in Colonial Singapore,” in Sketching the Straits: A compilation of the lecture series on the Charles Dyce collection ed. Irene Lim (Singapore: NUS Museums, National University of Singapore, 2004), 91-92. ↩

- Ibid., 104. ↩

- Ibid., 120. ↩

- Huang Lijie, “A long look back at Malayan art,” The Straits Times Community, 31 August 2013 <http://origin-stcommunities.straitstimes.com/show/2013/08/31/long-look-back-malayan-art> (Date of access: 5 September 2013>. ↩

- Flores, Past Peripheral, 9. ↩

- June Yap, “Perspectives: Curatorial connections, Southeast Asia: Three panels, two books,” Asian Art Archives, April 2009 <http://www.aaa.org.hk/Diaaalogue/Details/636 – diaaalogue_hidden_menu> (Date of access 11 September 2013). ↩

- Flores, Past Peripheral, 3. ↩

- Kwok Kian Chow, “The Bali Field Trip: Liu Kang, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi and Cheong Soo Pieng,” Channels and Confluences, The Literature, Culture and Society of Singapore in the Postcolonial Web Channels and Confluences <http://www.postcolonialweb.org/singapore/arts/painters/channel/12.html> (Date of access: 15 September 2013). ↩

- Huang Lijie, A long look back at Malayan art. ↩

- Flores, Past Peripheral, 25-26. ↩

- Ibid., 26. ↩