by Woho Weng –

The title of the exhibition Ties and Fragrant Lies is derived from a play of words with Thai fragrant rice, Thailand’s most well-known export noted for its delectable light aroma. It is an everyday staple in the diet of many Asians. The subversion in rhyme however signals a departure from the wholesome goodness image. The exhibition title encapsulates the criticality in the paintings presented by eight young Thai artists who pry open the gentle and virtuous façade of a country so often promoted by its tourism industry as the Land of Thousand Smiles and devotional spiritualism. What they reveal instead are the contradictions and vagaries of everyday urbanised life in current times.

Context and curatorial framework

At the onset, the artists are clear-minded in their intent to put up an exhibition to promote Thai art and culture. But their works fit in more as an intimate contemplation than a loud nationalistic campaign. After all, they deal with individualistic viewpoints and anecdotal observations concerning self and their immediate environment, rather than grand subjects such as national history and politics. What this exhibition offers is a topical look into a group of home-bred Thai artists whose painting practices are freshly molded by their local art academies and their psyche heavily shaped by religious teachings namely through Buddhism, one of the three pillars of Thai society. Born in the second half of the 1980’s all under 30, the artists are currently undertaking or have just completed a post-graduate course in painting at Silpakorn University in Bangkok. The university, founded in 1943, is instrumental in bringing about modern art practices in Thailand. Then the Dean of the Faculty of Painting and Sculpture, Silpa Bhirasri (aka Corrado Feroci, an Italian sculptor before he adopted the name change) effected a turning point in Thai art by introducing Western art and aesthetics into the curriculum of Thai students. Yet at the same time, he encouraged his teaching staff and students to retain their own culture and tradition and infuse them into their artistic practices.1 The transference of a hybridised model of making art becomes evident in the works of this new generation of painters once the creative impulses of the artists are framed by a spiritual sensibility centered on the notion of dharma inculcated from young. What at first glance may seem like unrelated subjects rendered in a Western academic style now fall neatly within three key tenets of Buddhist teachings – insatiable desires and attachment to worldly pleasures, misguided perceptions such as false ego and appearance and the illusion of a good life, and pathways out of worldly attachment and delusion. Therefore, reading the artists’ works through an analysis of iconography informed by their religio-cultural context works like a universal key. It cracks open the underlying connectedness of the paintings and unlocks their layered meanings. This interpretation augments with the raw statements written in English by the Thai artists about their concepts. The exhibition is essentially a snapshot of a successive generation of young adults struggling to come to terms with the physical world and their spiritual convictions.

The beast within

Urban life in a city is one flushed with easy access to every imaginable opportunities and conveniences. It offers an abundance of livelihood and lifestyle choices as well as materials and services to meet every desire and taste of city dwellers and visitors. Yet beneath such outward show of opulence and glitters, urban life is also littered with grits and traps. When a person is faced with excesses and over-stimulated desires, what becomes of his or her human nature? How does one contain the ‘beast’ within human nature? The artists bring to light that things are not what they appear to be.

Anchalee Arayapongpanit (born 1985) mobilises an alter ego in the form of an all-powerful woman who can capitalise on today’s easy access to affluence and life opportunities to chart her own destiny. Her paintings are larger-than-life portraits expressively done in her likeness with personae inspired by youth, pop culture and social media. Striking a pose with large penetrative eyes and pouting lips (identifiable with Angeline Jolie’s signature look, a popular Hollywood actress), the lone figure in the portraits bears no shades of the gentle and submissive demeanour commonly ascribed to Asian women in a patriarchic society. In Anchalee’s own words, her characters are “sometimes playful, sometimes fearsome, sometimes provocative”, seen in the paintings as flexing a tattoo on her toned arm, clutching a semi-automatic rifle or sliding up against a shiny-new motorbike in a tight leather outfit. Yet in her outwardly bid towards self-empowerment, the alter ego appears too self-indulgent in only satisfying her own desires and living up to her own image. In the pair of portraits titled 007 and 27 (Fig. 1A & 1B) which references the famed fictional British Secret Service agent and her current age, she has attained a new level of self-sufficiency. She is now both the groom and the bride. But this assuming of dual gender roles unexpectedly and poignantly let slip a psychological fissure of a limited self which excludes meaningful relationships with other people. There are also questions concerning her assumed characters. The double may have over-zealously taken on the façade of a foreign culture so much so that the liberated woman now looks like an anime character or a game avatar in the age of entertainment and cyberspace.

While Anchalee’s femme fatale is rooted in the here and now, Krissadank Intasorn’s muse acquires an antiquated mystic temperament. Krissadank (born 1986) is acutely sensitised to critical moments of life’s conundrums. His paintings capture the point before a rupture of latent desires and prurient thoughts, contained during the light of day by moral codes and cultural propriety but unleashed under the veil of the nocturnal through dreams, fantasies and art. The person is literally split in body and soul. The outcome of his or her choice is never settled – a liberation of spirit or a descent to lawlessness? In his works, the artist takes on the perspective of a bare-chested adolescent beauty, at once the seduced but also at risk of becoming the seducer, on the cusp of awakening to her sexuality and prowess as a self-determining woman or consummating in a frenzy of bodily and worldly pleasures. This tension is accentuated by the artist’s rendering of figures with traditional Thai tattoos and in Lanna art style done on indigenous materials such as Sa (mulberry) paper and wood panel. The deliberate appropriation of neo-traditionalism, pointing towards the stoicism of religion and tradition, plays up against the easy corruptibility of human nature. In The Red Full Moon and Tangle Song (Fig. 2A & 2B), the fair maiden has fallen to the dark side. She becomes a seductress under the ripening of a bloodied moon to ensnarl willing men with a luring musical instrument and a long mane of serpent-like tresses. Even the tiger, a symbol of power and virility, is incapacitated under her spell.

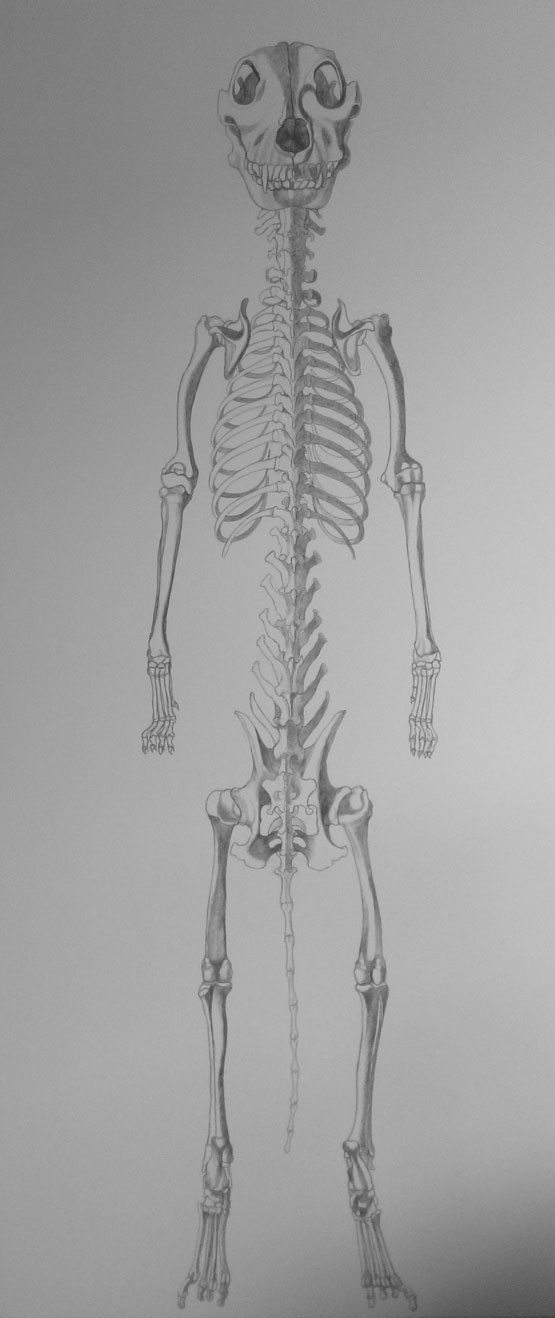

The Lanna demoness depicted in Krissdank’s paintings may as well shed her human skin and flesh and what is left behind would be the skeleton of a beast in Phansak Kaeosalapnil’s Passion in the Light work. In his latest set of paintings, Phansak (born 1984) examines the phenomenon of duality embedded in all entities via the notion of light and darkness to show the complexity of human nature and experiences. Every entity is a potential carrier of oppositional attributes, even in the plainest signifiers of white and black. In the ‘white’ canvas titled Passion in the Light (Fig. 3A), it is no longer registered as a site of goodness as it reveals the skeletal beast within humans. In the ‘black’ canvas titled Passion in the Darkness (Fig. 3B), it does not connote evil as it presents humans in their most vulnerable elemental form. It is a play of semiotics by reversal of assumed associations. In human experiences, people are drawn to pleasure without knowing its addictive effect. Conversely, they are repelled by pain or unpleasant experience without realising its value to teach them about compassion and empathy. Through this diptych, the artist reveals two layers of meanings. At one level, he exposes the falsity of surface appearance and forewarns the viewer not to take things at face value. At another level, he embraces the positive and negative attributes of an entity or experience as life-affirming forces.

Deprivation in the midst of abundance

Here lies one of the greatest contradictions of urban life in a city. Despite a place overflowing with people and materials, many city dwellers feel a sense of emotional and social isolation and emptiness, a disconnection with their environment and spirituality. There is a hidden catch in every choice.

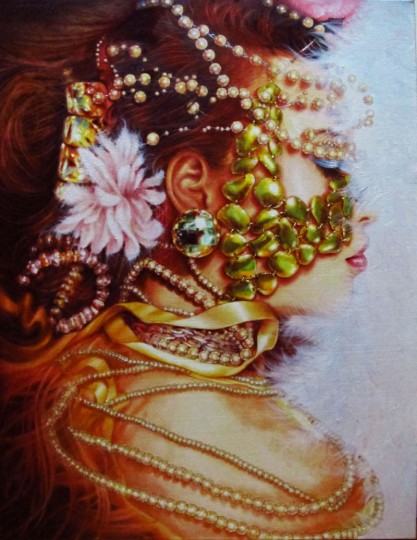

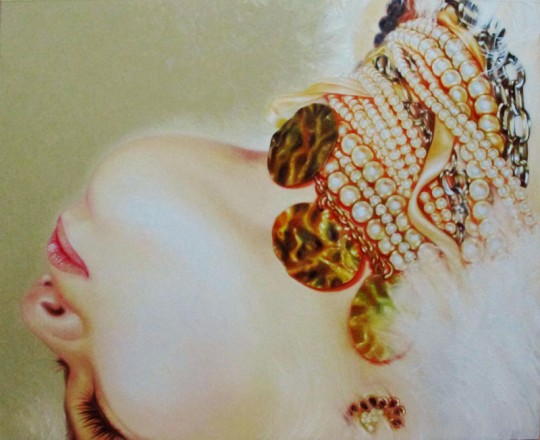

Suriwan Sutham (born 1985) addresses representations of feminine beauty in a consumerist culture, externalised through women dressed up in jewellery, accessories and make-up. Covered under a cloak of luxurious goods, a woman is made into an object of beauty herself. This outward presentation is often internalised and becomes her sense of self-worth, identity and value. At first glance, Suriwan’s paintings are pictorial frames of opulence, fitting as retail advertisement for high-end lifestyle. However, the accessories are piled on so heavily on the wearer that they literally bury her under like the accoutrements of entombment. Instead of complementing her look and worth, they empty her out and define her. In the Sleeping Beauty series of paintings (Fig. 4A, 4B & 4C), the woman with a perfectly made-up face displays no joy over her overflowing physical assets. Instead, she appears comatosed and becomes an inanimate object in a still-life painting. The pursuit of material possession indeed works like a drug to the mind. Not only does the desire compel the whole being to crave for one pleasurable high to another, it only numbs the mind to other dimenisons of meaningful living. What is picturesque and alluring at first turns out to be a forewarning against material obsession and vanity.

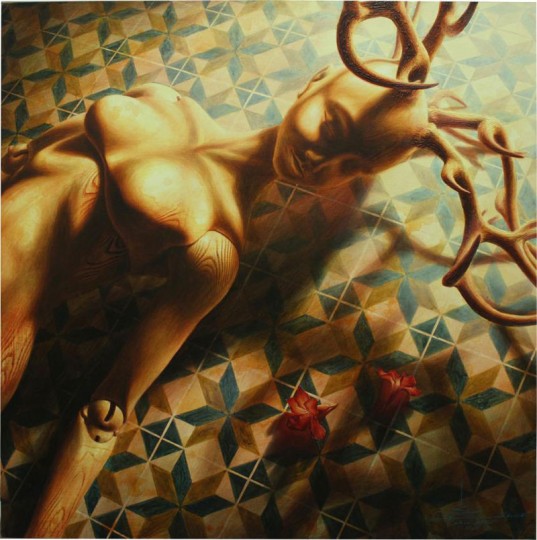

Manit Srisuwan (born 1985) goes a step further in representing people’s conflicted state of mind in an affluent urbanized life. In his world, the humans have morphed into a different creature. Manit’s paintings are deeply contemplative and atmospheric. They show a retreat into an inner sanctum. People, depicted as alone and pensive, are revealed as lifeless human casts akin to mannequins seen in departmental stores or plaster models used for life drawing. They lie sprawled on uniformly patterned floor littered with remote organic objects, illuminated dimly with chiaroscuro effects. The paintings are allegoric, referencing the relation of a person’s inner human existence with the outside physical world. A human being can turn into an automaton of his or her own desires and ambitions fuelled uncontrollably by the urban lifestyle and its demands. However his works are not all bleak and pessimistic. The artist has suggested a way out of this predicament– to take a moment of reverie, to lie low and to stay grounded, to be connected with one’s human nature and nature at large. In Wilted Flower (Fig. 5B), a decapitated Roman plaster head stares forlornly at a ball of wilted chrysanthemum flower which shares its dislocated state. In Deer Lady 3 (Fig. 5A), the woman figure’s head has sprouted a pair of deer antlers while she looks pensively at a pair of frangipani flowers strewn on the floor. She is taking time out to locate an inner balance.

The path lost and the way out

Living in an urban city can also bring on a detachment from tradition and culture, religion and spirituality, without which life can feel empty and purposeless. Having an awareness of the ill-effects of urban life as shown in the above sub-themes is a necessary first step towards a meaningful and fulfilling life.

Pruethinan Kamalas Na Ayudhaya (born 1987) is singular in his vision to study and capture traditional Thai architecture. He focuses his attention on the roof tiers and decorations of Buddhist temples in various states of deterioration. Pruethinan’s paintings are a telescopic shot of these structures taken from ground up and contrasted against the open sky. This upward gaze is a form of reverence because he considers these buildings as national treasures and the glory of a nation. There is beauty and value in their wasted state. They mark the passage of time and hint at a poignancy that even the houses of gods cannot escape the phenomena of impermanence. The state of disrepair also directs attention to the urgency to conserve these national and cultural heritages. The artist accentuates this urgent need by flitting loose pieces of tiles and ornaments off the roofs of these temples. In his latest Faith painting (Fig. 6), traditions and the need to preserve them take on a mystical tone. The spire at one end of a roof tier is seen trusting skywards while a sprinkling of yellow chrysanthemums rains downwards, both framed against large concentric rings of yellow-tinted clouds. The halos of ring clouds allude to a heavenly presence. The placement of the roof tier against it accords an elevated status to Buddhist temples and traditional architecture. Chrysanthemum flowers are a common offering for prayers. Their withered state and loose petals suggest a lamentation of the plight of traditions. The artist infers that it is a message from heaven which we mortals can ill-afford to ignore.

In contrast to Pruethinan’s use of artefacts of historical and cultural significance, Wilawan Saowang (born 1984) deploys a limited set of common and unremarkable objects and processes – locks and rusting on doors and gates – to invoke a complex web of notions relating to boundary, time and the trespasses of time across boundaries, shifting perspectives of looking inside out and outside looking in. In a simple freeze frame of a shiny padlock hooked over a pair of rusty metal loops as seen in the Lock diptych paintings (Fig. 7A), Wilawan draws out key subjects in Buddhist teaching – permanence and impermanence of both physical and mental states, mental paradigm inverted at the flick of a change of mind. What is seen as a locked enclosure can be undone with the passage of time. A brand new padlock will eventually rust over time. And while this duration may seem lengthy, it is but an instant when measured over a millennium. The world as we have known it has existed eons of time before this moment and will continue to exist many eons after. In Believe (Fig. 7B), the artist has layered over an additional element in her work by interrogating he boundaries of traditions. Here, there is a double locking of the door of a cabinet painted with traditional floral motifs. Its meaning is ambiguous – does this signify a loss of traditions or freedom of expression boxed in by traditions? Whichever is the case, the division is about to collapse as the door and its hooks are worn out. Drawing up a boundary in the first place, whether physical or mental, is both artificial and futile.

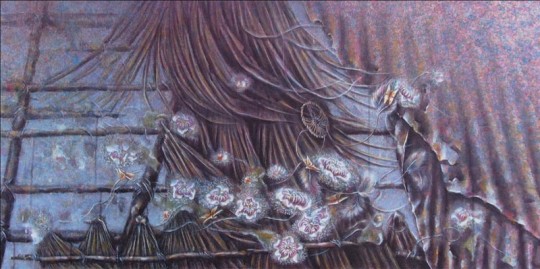

Likewise, Supparak Nopparat (born 1986) deals with profound concepts with the most mundane subjects. She is interested in the natural laws of life on Earth – the cycle of life and death, and geotropism (aka gravitropism which refers to the growth of plants in response to gravity). For the longest time, humankind has found in nature a representation of the ideal and a resource of life’s greatest lessons. For instance, a life cycle is played out at the cellular level of generation with decay and regeneration happening in a blink of an eye. But industrialisation and modernisation have made us disconnected with nature and blind to natural forces. The artist’s observation is articulated in her meditative paintings of plants growing in abandoned sites and along sidewalks. In My Care and Have a Good Dream (Fig. 8A & 8B), zinc fences rust and eventually collapse in accordance to gravitropic law, while shrubs and grasses covered under them twist their way out of these man-made obstacles and defy gravity in accordance to their anti-gravitropic nature. It is an epic interplay of life and decay performed at the commonest of unnoticed places.

Conclusion

The significance of this exhibition lies in what this new generation of Thai painters collectively present. They tune into everyday life issues from their immediate environment and consider them as worthy subjects for their art. They turn inwards through their paintings to search at the essence of the matter, instead of extending outwards to place their works on a larger political, historical or national context. They have tapped on the seemingly inexhaustible potentiality of painting to mark their struggles. Although the issues they invoke are not new, they add on nuanced observations to the complexity of human nature and experiences. What is pervasive is the presence of Buddhist philosphy undercutting the creative impulses of these Thai artists. It gives a differentiated inflexion to the painting practices in this region. Despite the collective wisdom from elders and history, each generation must fight their own battles and find their own footings in an increasingly shifting and complex world. How these emerging artists develop from here – extend on their current practices, carve out new paradigms or even challenge the practices of their predecessors – will be a subject of considerable interest and for future studies.

Woho Weng graduated from the MA Asian Art Histories programme in 2012. This is a curatorial essay that accompanies the exhibition Ties and Fragrant Rice, co-curated by Woho Weng and Joey Soh. Ties and Fragrant Rice will be shown at One East Asia, Singapore, from 4 June to 25 June 2013.

————————————————————————

Select Works for Ties and Fragrant Lies Exhibtion

Krissadank Intasorn

Phansak Kaeosalapnil

Suriwan Sutham

Manit Srisuwan

Pruethinan Kamalas Na Ayudhaya

Wilawan Saowang

Supparak Nopparat

————————————————————————

- Somporn Rodboon, “Developments in Contemporary Thai Art,” in Art and Social Change: Contemporary Art in Asia and the Pacific, ed. Caroline Turner (Canberra: Pandanus Books, 2005), 278–9. ↩